You knew this post was coming. The only surprise is how long it took me to get around to writing it! It’s dedicated to my former colleague, the evolutionary anthropologist Lia Betti, who suffered through years of marking undergraduate essays on this topic with me.

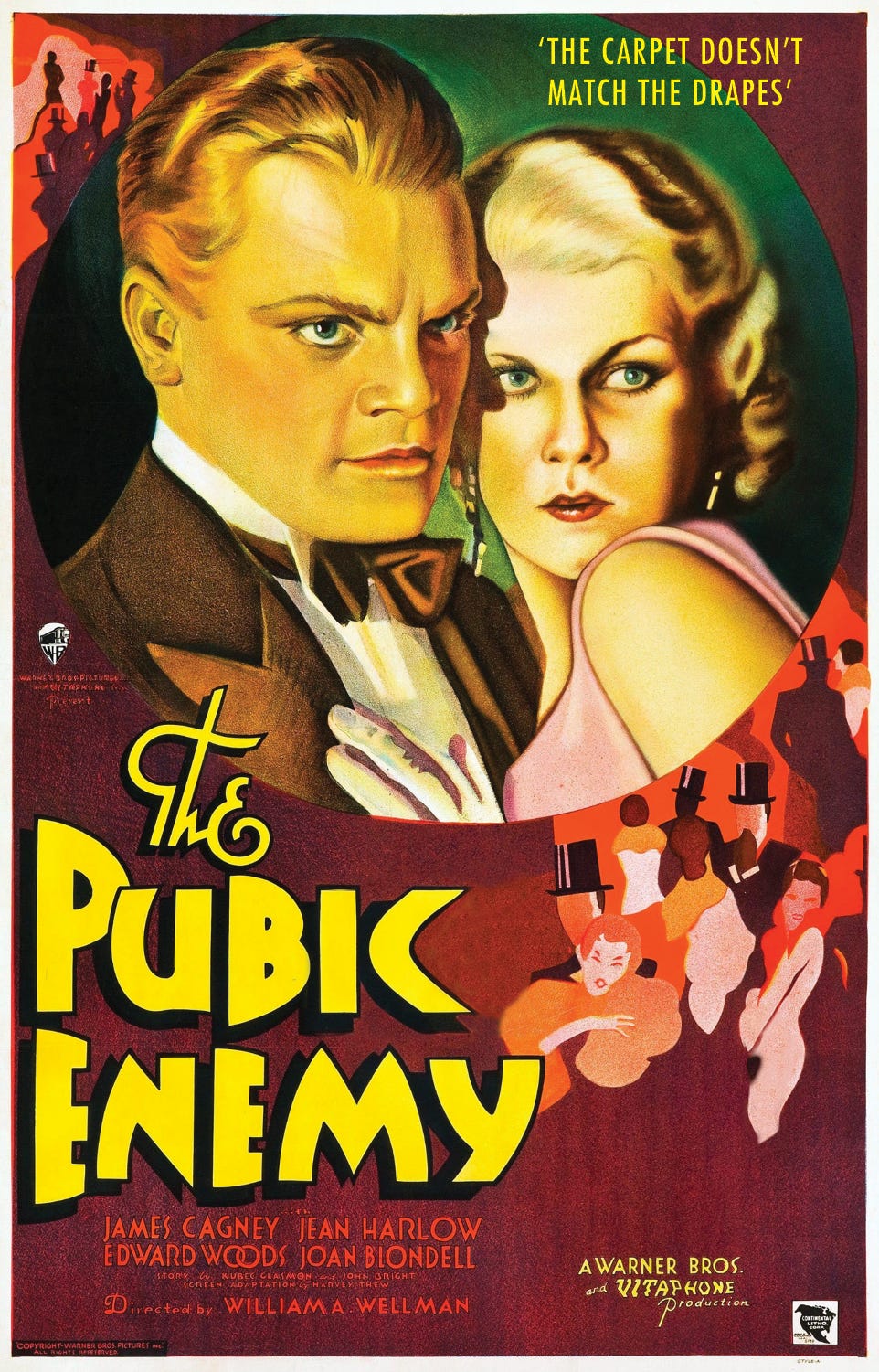

If you’ve been on the tube in London recently, you will likely have seen the following ad. I did a double take when I saw it, not primarily because it was advertising pubic hair removal, but because it was clearly advertising it for men. Yes, just so we’re clear, Gillette is now advertising an ‘intimate pubic hair and balls’ trimmer.

As a woman with pubic hair long enough to plait and add decorative beads to,1 I am clearly deeply out of touch with cultural mores on this topic, but I can’t imagine most men of my acquaintance allowing such a product within striking distance of their balls. Therefore, I assume that such a product is not for ‘old’ men (i.e., men over the age of 50), but all those ‘new’ men concerned about the state of their manscape.

It’s difficult to know how many people remove their pubic hair, although evidence suggests that it’s fairly widespread, albeit more common amongst women than men cross-culturally. For example, a study by the anthropologists Lyndsey Craig and Peter Gray drawing on the Human Relations Area Files (a large anthropological database of cultural practices around the world), found that women were more likely to remove their pubic hair than men, for reasons of perceived cleanliness and attractiveness. However, female pubic hair is far from universally abhorred. For example, amongst the Kwoma of Papua New Guinea, thick and luxuriant pubic hair is considered a ‘traditional mark of beauty’.

In any case, although the practice is clearly gendered, pubic hair removal amongst men is also relatively common—and getting more common by the day, if the Gillette ad is anything to go by. However, it’s worth noting that male pubic hair removal is not a new practice. For example, it has a long history in Islam for both sexes as part of rituals of cleanliness.

Conversely, in western contexts, the ‘back, sack and crack’ wax2 was popular in the gay community well before it became mainstream—although both gay and heterosexual men appear to be motivated by similar concerns, namely: a desire to improve their attractiveness. A key factor seems to be the perception that it makes one’s genitals look larger—a topic I first saw discussed in the noughties’ stoner classic Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle.

So why on earth do we have pubic hair and why do so many people feel compelled to remove it? From an evolutionary standpoint, anthropologists remain relatively clueless about why humans evolved such different hair from our primate relatives, with our thickest and most visible body hair concentrated primarily on our head, underarms and genitals. However, a number of theories have attempted to explain our relative hairlessness, including the thoroughly discredited aquatic ape theory, the equally dubious naked love theory, and the not-especially-convincing regulation of body temperature theory and parasite reduction theory.

None of these theories explain the existence of pubic hair. In fact, as Pagel and Bodmer, who proposed the parasite reduction theory, acknowledge, ‘The retention of pubic hair poses a challenge for the ectoparasite hypothesis, as it provides a warm and humid environment favourable to ectoparasites’.3 Instead, they suggest that pubic hair is the result of sexual selection,4 and reiterate theories emphasising its potential role in pheromonal signalling.

According to this school of thought, pubic hair provides an olfactory signal of reproductive state, because it’s concentrated on parts of the body that are dense in apocrine sweat glands, the scents of which are captured by hair. The problem with the pheromonal signalling theory is that the existence of human pheromones is hotly debated.5 However, what does seem evolutionarily significant is the role that pubic hair plays in visually signalling reproductive fertility. After all, it’s a secondary sex characteristic that only appears at puberty.

In light of its association with sexual maturity, Craig and Gray observe that the human tendency to want to remove pubic hair is somewhat puzzling.6 For example, pubic hair has long been associated with sexuality in western contexts, given that the dividing line between art and pornography was basically premised upon it. A case in point is the nudist movement in the UK, which became popular from the 1930s. According to the historian Annebella Pollen, to pass the censors, photographic retouching was required of the genitals, resulting in photos of frolicking nudists with a distinctly Barbie-like appearance to their groin.

Although the associations of pubic hair with sexuality and obscenity are significantly stronger for women than men, it’s worth noting that pubic hair was rarely depicted in artistic nudes of either sex until the nineteenth century—Michelangelo’s David being a notable exception.7 Indeed, as I recounted in my discussion of the French obsession with budgie smugglers, the only reason why men flaunting their speedos on Bondi Beach in the 1960s managed to escape public indecency charges was that while their speedos might have outlined their meat and two veg, they didn’t expose pubic hair.8

In fact, as Ramsey and colleagues note, one popular theory regarding the contemporary fixation with removing pubic hair is that it’s a side effect of historical efforts to censor it. Given that pubic hair was a visible signifier of porniness, porn producers simply removed it as a way around the censors. Over time, hairless vaginas became increasingly normalised in porn, and men started to associate hairlessness with eroticism. Aided by the ubiquity of online porn and its broader cultural influence on sexual mores, along with the purely anecdotal (and frequently contested) claim that hair removal increases sexual sensation, we ended up in a situation where pubic hair removal has become commonplace in many western contexts, first for women and increasingly for men.

That said, the significance of porn has been disputed, given the frequent emphasis on cleanliness as a justification for pubic hair removal—although like many of our cultural practices conducted in the name of hygiene, there is nothing unclean about pubic hair and removing it has a host of health-related side effects. Instead, the view of pubic hair as unclean is clearly related to our tendency to shed it at an alarming rate—something that the humorist David Sedaris discusses at length in his essay ‘Naked’, as his brief stint at a nudist colony quickly clarified why members were required to carry a towel with them at all times to sit on.

Still, if history has shown us one thing, it’s the fickleness of our norms regarding body hair of all types—both above the neck and below the belt. In fact, at the very same moment that Gillette is encouraging men to remove their pubic hair, there is talk of an impending ‘pubeaissance’ amongst women, partly inspired by Björk’s recent appearance on the cover of Vogue Scandinavia wearing a merkin (a.k.a. a pubic wig). However, this cycle seems to reliably occur every decade or so, when a celebrity—actually, mostly just Gwyneth Paltrow—declares that pubic hair is out or in and media pundits celebrate the death or rebirth of the ‘bush’ accordingly.

In the end, I guess there is little better illustration of the human capacity to turn literally everything into a symbol than our obsession with pubic hair—one of the most private yet simultaneously public of symbols. As the literary scholar Karin Lesnik-Oberstein notes, choosing to remove pubic hair, and, equally importantly, choosing not to remove it, are both saying something, whether we want them to or not.

But if you do choose to manscape, or to mow your ‘lady garden’, health and hygiene should not be your motivation for doing so, because while we might not understand why we developed pubic hair, it evolved for a reason. Oh, and one final word of advice. If you’re a redhead wanting to shave your pubic hair, proceed gingerly.

Related posts

Some of you may recall that I am a regular swimmer, thereby begging the question of whether my bikini line looks like Bo Derek’s hair in Ten. All I can say is that I wear boy-leg swimming costumes, thereby avoiding the problem entirely.

Fun fact: the back, sack and crack wax is also known as the ‘Manzilian’—a riff on the Brazilian wax popular amongst women.

Oddly, the list of ectoparasites found in pubic hair does not include the beaver beetle. Boom! (Brett Davis: that one’s for you.)

Sexual selection is when a trait is selected through mating preferences rather than the natural environment. Basically, the former directly increases reproductive success and the latter does so indirectly, because one makes you more shaggable in the eyes of the opposite sex and the other makes you more likely to survive long enough to shag. Personally, I don’t think that sexual selection brings us any closer to understanding the existence of pubic hair, because both men and women have it in equal volumes (unlike, say, visible facial hair). Also, even in societies where people wear comparatively few clothes, the pubic region is often (albeit not always) covered, so you’ve already reached the shagging stage by the time you see someone’s pubes.

This, of course, is why dogs typically head straight for your groin when you meet them.

Although admittedly less puzzling than the briefly popular practice of vajazzling.

Interestingly, it was Michelangelo’s unusual interest in depicting pubic hair on his male sculptures that has apparently enabled art experts to identify him as the sculptor of two Renaissance-era nudes.

Although that’s somewhat debatable, as this image attests. I suspect that part of the reason why male pubic hair is less sexualised than female pubic hair is that it’s often more difficult to distinguish from other body hair.

It's all rather odd. I can understand trimming - after all, going further up the body, a trimmed beard looks better than the full Ned Kelly - but complete shaving?

Particularly after having children I found complete shaving to be weird. I'm not attracted to childishness of any kind.