This piece is dedicated to Nadine Beckmann, who first alerted me to the rules about speedos in French swimming pools. I haven’t been able to completely get to the bottom of this mystery, but hopefully other anthropologists can take up the baton and solve it once and for all!

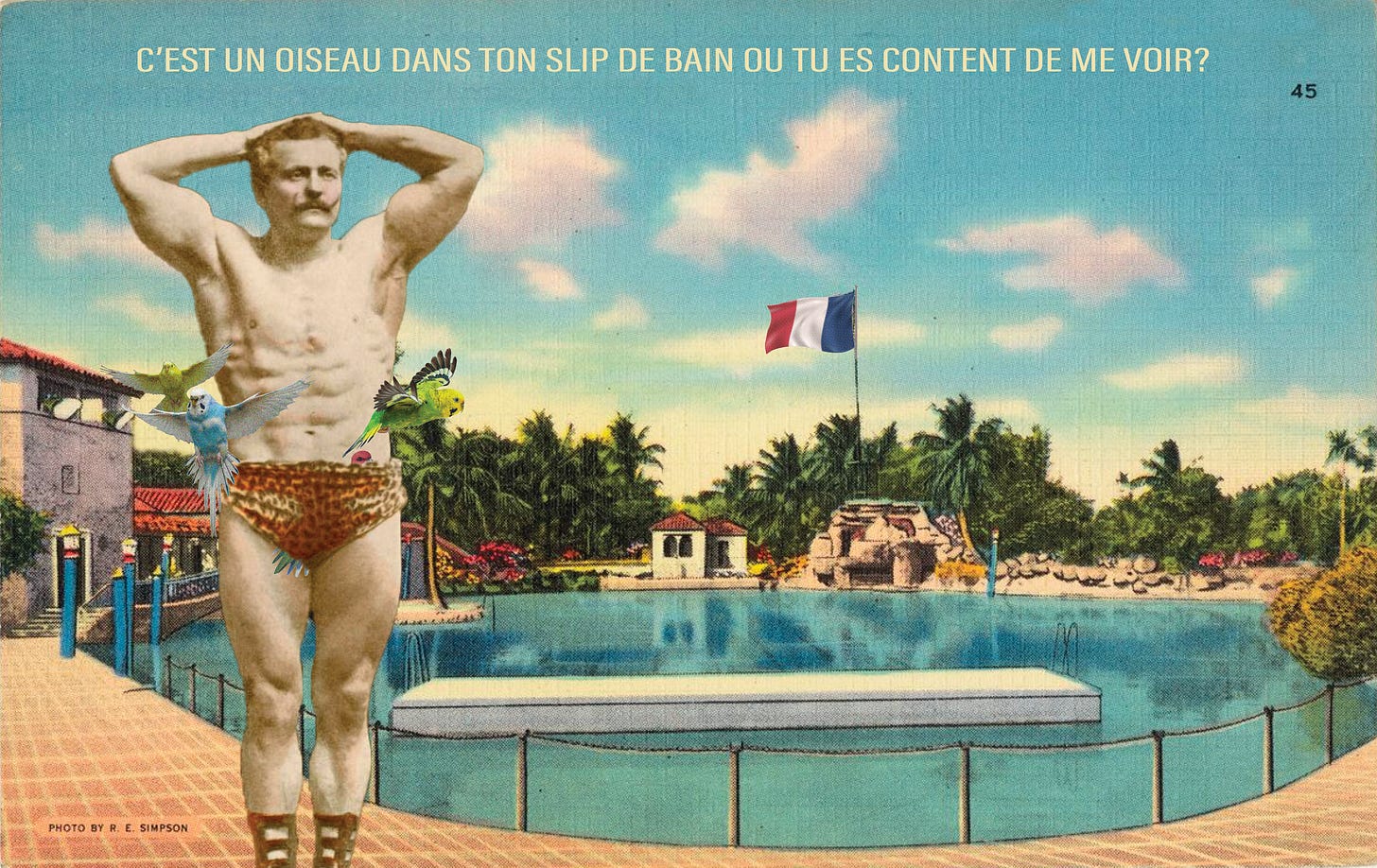

Men visiting France during the summer often receive an unpleasant surprise when venturing into public swimming pools. They arrive at the local lido ready to cool off from the heat, only to find that there are strict sartorial rules surrounding male attire in the pool. If they want to go into the water, in most public swimming pools their only option is to don the male version of an itsy bitsy teenie weenie yellow polkadot bikini: namely, a pair of speedos, or, as they are affectionately known in their (and my) country of birth, ‘budgie smugglers’.1

Reports abound of foreigners being forcibly removed from French swimming pools for refusing to abide by the rule. To quote from a 2009 article in The Guardian, ‘As he lowered himself into the shallow end, the pool attendant screamed that his oversized attire was outlawed. Scoffing at the ridiculousness of the rule he swam to the middle of the pool only to be fished out by the lifeguard and three other attendants who “fetched a big hook for fishing out drowning people and hauled me in”’.

These days, fishhooks are rarely needed, primarily because French pool attendants are widely aware that le barbares étrangers2 are ignorant of the requirement. Foreigners are therefore frequently subjected to the French equivalent of a ‘no speedo, no service’ announcement well before they set foot in the water, and speedo vending machines are now a ubiquitous feature at most French swimming pools. There, for the price of five euros, tourists can purchase a tiny genital covering that most will abandon immediately upon departure from the pool,3 never to revisit again (except mentally, when reliving the abject humiliation of the experience).

As one American tourist, Gabe Gunnink, later described his visit to a French swimming pool:

‘The process of entering a French pool is unnervingly similar to enduring airport security: it takes way longer than it should, the workers are disgruntled at best, you’re guaranteed to feel somewhat violated, and specified items must be neatly stowed in a 7.5×8 inch package. In this situation, though, the items aren’t your liquids and gels but your genitals, and the 7.5×8 inch package isn’t a Ziploc bag but a swatch of fabric I can only assume is fashioned from otherwise unusable scraps at the trampoline factory’.

In this respect, France stands in stark contrast to various other countries, where the more common response has been to ban speedos from swimming pools on the grounds of sparing other pool goers the sight of men in budgie smugglers. For example, in 2009, Alton Towers Resort in the UK reportedly prohibited speedos on the grounds that ‘this small brief style is not appropriate for a family venue’. Indeed, the Sydney Morning Herald documents that when speedos were first introduced in Australia in the early 1960s, men cavorting in their new togs on Bondi Beach occasionally found themselves up on indecent exposure charges for the same reason.

So why on earth do the French insist on budgie smugglers in swimming pools? The universal reason given is hygiene. The most common explanation is that board shorts, unlike speedos, can be worn outside the swimming pool,4 thereby attracting dirt and debris, which then contaminates the pool’s pristine waters. To quote Suncamp Holidays, ‘A pair of tight-fitting swimming trunks holds on to less dirt and people don’t usually wear them when wandering around the city for the day’.

One needn’t be the anthropologist Mary Douglas, who has written extensively about the symbolic meanings of ‘dirt’, to perceive this explanation as suspect. As Janine Marsh of The Good Life France blog notes, ‘I can only assume they have not visited the beaches of the south of France where barely there pants are much in evidence off and on the beaches… [And] we all know that little kids wee in the pool,5 so it’s a bit of a moot point to worry about a bit of dust on a pair of pants really when you’re using a public pool’. Likewise, plenty of women wear bikinis all day while on holiday, throwing a sarong over the top when they are not swimming or sunbathing, so the logic of banning board shorts on the premise that can’t be worn outside the pool doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

My suspicion is that despite its ubiquity on the internet, this explanation is largely the product of the 2009 Guardian article, which quotes a Parisian pool attendant as saying, ‘Small, tight trunks can only be used for swimming. Bermudas or bigger swimming shorts can be worn elsewhere all day, so could bring in sand, dust or other matter, disturbing the water quality’.

An expedient, post-facto feel pervades the other justifications for the practice – such as the idea that speedos are more hygienic because they dry faster. To quote the Oui in France blog, ‘Frequent swimmers aren’t going to wash their suit daily, so a fast-drying suit is best’. Another ludicrous explanation occasionally trotted out is the environmental basis for the rule. For example, Suncamp Holidays advises (apparently with a straight face), ‘loose swimming trunks hold on to a lot more water than the tight-fitting versions. When you get in and out of the water a few times, that can save many litres of water’.

Others, still, insist that the proscription against swim shorts dates back to an archaic rule from 1903 – a claim that seems to have its roots in a 2015 article in Esquire suggesting that swim shorts were banned on hygiene grounds in the early twentieth century. The problem is that this statement has no clear factual basis. According to the historian Ann-Louise Shapiro, there was a public health law enacted in France just after the turn of the century, but in 1902, not 1903. Under the legislation, smallpox vaccination became mandatory, reporting requirements were put in place to help contain contagious disease, and departments were divided into sanitary wards, with new powers for mayors to ensure the healthfulness of their local population.

In 1903, the Minister of the Interior did issue a circular defining the scope of mayoral responsibilities for the public health of their community, which covered topics such as ‘the salubrity of dwellings, the prevention of contagious disease, general sanitary standards, and penalties’. While it’s entirely possible that hygiene in swimming pools was discussed in the circular, I very much doubt that bathing suits were a focus, beyond, that is, the need to actually wear one.

According to the sports historian Thierry Terret, part of the initial impetus for creating public swimming pools in Paris was the desire to improve people’s personal hygiene by encouraging them to bathe. At this time, the physical benefits of swimming in improving people’s fitness were seen as secondary to its sanitary benefits in getting them clean. Another consideration was the desire to stop people bathing naked in inappropriate environs – primarily, the Seine. However, people’s refusal to cover their genitals continued to be a problem once public swimming pools opened – at least if the volume of contemporaneous complaints about nakedness is anything to go by.

To quote from a missive by the mayor of Loyone,

‘I have instructed those in charge of the swimming school to make sure that all bathers are equipped with swimming trunks. It appears however that this is not the case in the indoor pools. A crowd of people were seen naked outside the pool on each side of it and even right up to the harbour entrance. I received numerous complaints about it’.

In this environment, where mayors were desperate to get swimmers to cover their genitals at all, the length or tightness of said covering was surely a moot point!

Another reason to be suspicious of claims that the rule dates to 1903 is that Speedos were not even a twinkle in their inventor’s eye at this time. Developed in Australia in the late 1950s, they were not publicly available until 1961. Instead, swim trunks were the norm, as the above 1884 illustration of a Parisian public swimming pool makes clear. Likewise, photos from beaches in Normandy from the period between 1900 and 1938 illustrate that the tank suit was ubiquitous for both males and females for the first half of the century.

Board shorts, the cause of so much contemporary ire amongst French pool attendants, were not actually invented until the 1950s, and didn’t become widespread attire amongst swimmers until the 1980s. An innovation amongst surfers, reports indicate that part of the impetus for their development was to reduce the hair removal and chafing that occurred from surfers constantly rubbing their legs against the paraffin wax on their boards.

In fact, it’s possible that body hair, or, rather, pubic hair, is an untold part of the story of why speedos came to predominate in French swimming pools. For while board shorts might protect body hair from unwanted removal, speedos keep said body hair – at least that emanating from the pubic region – from unintentional removal.6 Arguably, when it comes to pubic hair containment, they are more reliable than board shorts, which, being longer and looser, allow for easier escape, unless worn over briefs – whose presence is, for obvious reasons, hard to confirm.

Interestingly, pubic hair is part of the speedos story in Australia. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, the charges against men wearing budgie smugglers on Bondi Beach in the 1960s were ultimately dismissed on the grounds that the swimming briefs didn’t reveal pubic hair – so they were, quite literally, a hair’s breadth from indecency.7 Viewed in this light, speedos have two main functions: to cover genitalia and to contain pubic hair.

Adding credence to the pubic hair theory is the fact that swim caps are a requirement in most public swimming pools in France – even for men with short hair. This would suggest that speedos are part of a repertoire of instruments used by French pool attendants for hair control, which, being ‘matter out of place’, epitomises symbolic ‘dirt’ in Mary Douglas’s sense, but also has concrete consequences for pool sanitation, because of its tendency to clog drains.8

The problem is that if your goal is to eradicate loose hair in swimming pools, it’s a little short-sighted to focus exclusively on the head and genitals (as Marta Ibarrondo’s cartoon illustrates). A more logical form of swimwear would be full body suits – basically, the burkini: the very same attire currently banned in French swimming pools.

Although burkinis are seen to violate the principle of secularism, cases where women have been fined for wearing them suggest more complex forces at play. According to a 2016 report, a woman wearing a burkini on a beach in Nice received a ticket for not wearing ‘an outfit respecting good morals and secularism’. While the suggestion that a swimsuit designed with modesty foremost in mind does not respect ‘good morals’ strikes the uninitiated observer as somewhat bizarre, it indicates that moral value is attached to swimwear designed to celebrate, rather than hide, the human body.9

If the burkini symbolises the antithesis of liberté, égalité, fraternité in the minds of French legislators, speedos arguably symbolise the opposite. Certainly, there is something democratic to the notion that the natural lumps and bumps of the human body, whatever its shape and size, are nothing to be ashamed of – especially in contrast to the widespread Anglophone idea that speedos are indecent, unless displayed on toned, youthful bodies.10 But that very same attitude towards the human body holds in other European countries that are much more relaxed about male (and female) attire in swimming pools,11 suggesting the limits of this explanation.

In sum, there are a variety of potential reasons for the French obsession with budgie smugglers in swimming pools, from pubic hair control to the ways swimming attire has become caught up in the assertion of ‘French’ values. But one thing’s for sure: the rules around speedos are not due to their hygienic superiority to board shorts, despite frequent claims to the contrary. Indeed, given the oft-reported delight that pool attendants take in forcing Brits, Americans and Australians to comply with the rule, it wouldn’t surprise me if humiliation as much as hygiene is part of the ongoing attraction budgie smugglers hold for the French – at the very least, it is clearly a happy side effect.

Related posts

For the record, they are known by many names in Australia, from ‘dick togs’ (the favoured term in Queensland, my home state) and ‘dick stickers’ to more euphemistic appellations such as ‘lollybags’, ‘banana hammocks’ and ‘budgie smugglers’. Budgie is, of course, short for ‘budgerigar’, a type of Australian parakeet.

I know I’m doing my best to give the impression that I speak French, but I actually don’t, despite having completed not one but two introductory French classes when I lived in Canada.* Google Translate and Istvan Praet are to thank – and also, obviously, to blame if I’ve mucked anything up.

*My first attempt was a failure based, I’m convinced, on the ‘loosey-goosey’ (his words) approach of my first French teacher, who had a syllabus that he promptly ignored for the entire semester. The attrition rate was so high that only ten percent of us remained by the end; I passed through sheer gratitude on the instructor’s part. The second attempt was a figurative and literal failure based, in part, on the fact that my French teacher would wince every time I tried to speak – my Australian-accented French was apparently an abomination to her Parisian ears. Oh, and probably the fact that I have absolutely no talent for languages has something to do with it as well. For the record, I found French just as hard as Korean, despite the latter having an entirely different sentence structure and writing system.

Quite literally, in some cases. A friend’s partner was once offered a discarded speedo by a helpful French pool attendant when they ventured forth to a public swimming pool and discovered the requirement. They politely declined and went to the local river beach instead.

This is a bizarre explanation, even when considered on its own terms. As Gabe Gunnink notes, ‘The rationale, apparently, is to ensure that no one walks in off the street and contaminates the pool with his dirty street-shorts. In other words, you are quite literally required to wear something so indecent the staff knows you wouldn’t dare wear it in public’.

Still, surely if one is going to ‘oui’ in a pool, the best place to do it is in a French one (sorry).

In his essay ‘Naked’, based on his sojourn at a nudist colony, David Sedaris provides an eye-opening account of just how much pubic hair we shed, thus necessitating that naturalists (well, considerate ones) carry around a towel to sit on in order to avoid leaving a trail of hair behind them. Personally, I think undies are easier and safer (what if you have cats?!?), but that’s just me.

Although the distinction between pubic hair and body hair strikes me as more theoretical than real if the man is particularly hairy, leading me to wonder how exactly judges determined this.

Plus, it’s pretty unpleasant to receive a mouthful of it while swimming laps, which is basically the underwater equivalent of wrestling with cobwebs.

Although that celebration only goes so far, with a balance between full coverage and outright nudity required. In 2022, the city of Grenoble in south-eastern France controversially lifted both its burkini ban and its ban on women swimming topless, only to have the bans immediately reinstated by the courts. To quote one critic of the bans, ‘Our fight is not just about our right to wear a long costume but also for those who want to swim topless. It’s a true fight for feminism’.

In Australia, budgie smugglers have apparently made a comeback, but primarily amongst men wanting to show off their toned physiques. Likewise, North American men with an abiding love of speedos basically have to go through a process of publicly coming out. And as we already know, Brits and Aussies have occasionally banned speedos outright on the grounds of indecency.

Germany springs to mind. Every year growing up, we would go camping on Magnetic Island – a tropical island just off the coast of Townsville. And every year, hordes of German tourists of all shapes and sizes would descend on the island and sunbathe nude. To the amazement of my siblings and I, the more intrepid ones would hike naked, wearing only hats, boots and backpacks, despite the risks from the sun (Townsville has the highest rate of skin cancer in the world) and snakes (Queensland is home to two of the most venomous land snakes in, you guessed it, the world).