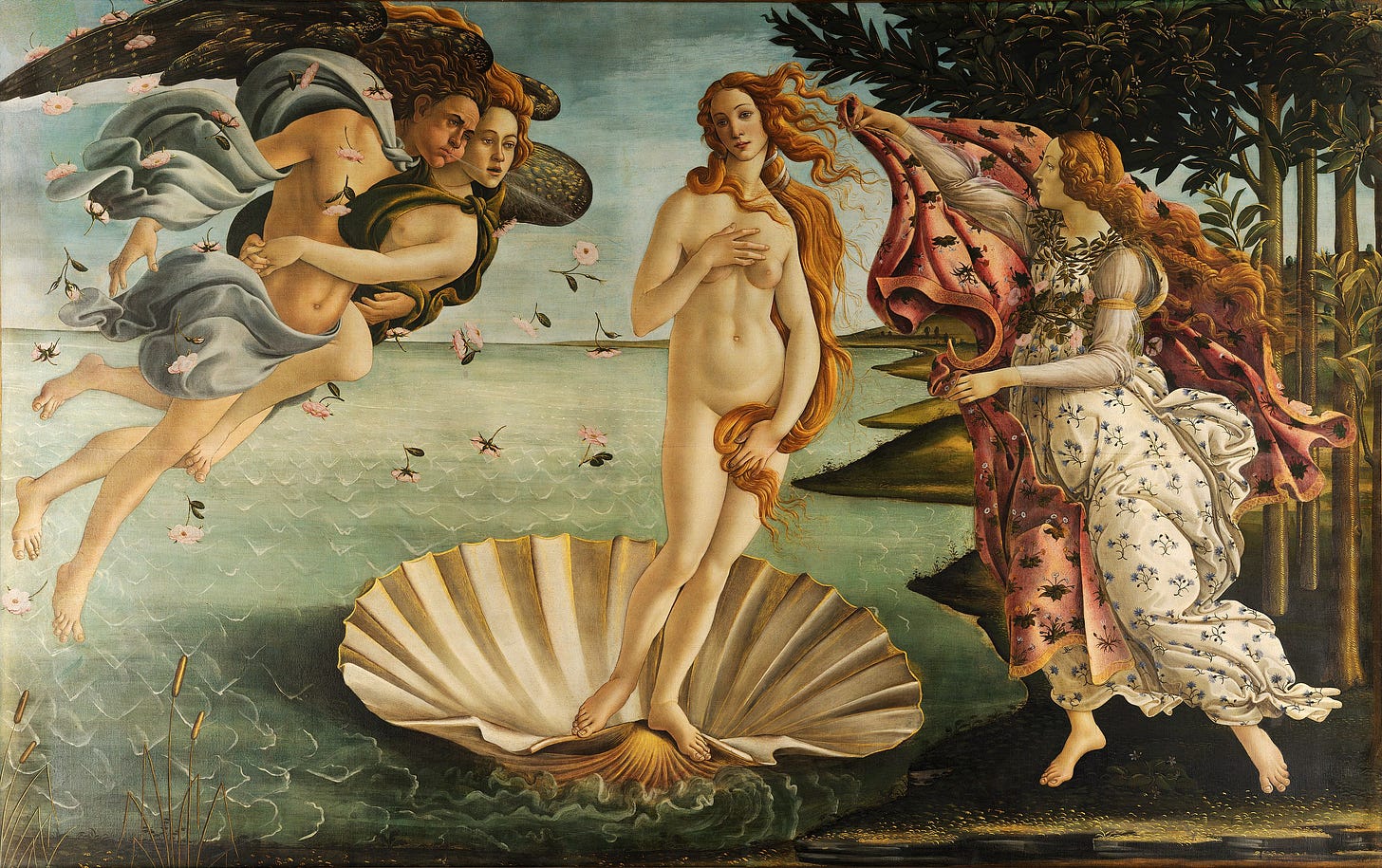

Recently, my husband and I visited the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and noticed a common theme in the sculptures and paintings of nudes: many were missing both pubic hair and areolae.1 Given that visible pubic hair has long been seen in Europe as a marker of obscenity, its absence was little surprise, but we were flummoxed by the lack of areolae. While many Renaissance paintings featured women with pert bosoms, they mostly had erect, areola-less nipples – including what is arguably the museum’s most famous painting: Botticelli’s ‘The Birth of Venus’.

The painting includes three motifs regularly found in depictions of female nudes: the ‘nip slip’, the artfully placed hand that simultaneously conveys modesty and titillation,2 and the veil of hair that felicitously covers key bits. But both the nipples depicted (that of Venus and the goddess Aura) are areola-less. Conversely, while we cannot see the god Zephyrus’s nipple due to a strategically placed flower, based on Botticelli’s painting of ‘St Sebastian’, we can safely assume that an areola is hiding under it.

Venus, long considered to be the ideal representation of female beauty, is particularly prone to being depicted sans-areolae – as Giorgione’s ‘Dresden Venus’ and P.J. Cazes’ the ‘Birth of Venus’ illustrate. However, while the practice of removing areolae is unquestionably gendered, some painters took a more democratic approach, simply choosing to leave them off everyone, male or female (e.g., Rubens’ ‘The Four Continents’).

This would suggest that the areola is – or at least was – seen to run counter to the aesthetic ideals of Renaissance-era Europe. But why? Disappearing the areola is of a very different order than erasing pubic hair because the latter can actually be removed. Nipples and areolae, on the other hand, form an integral set: the ‘nipple-areola complex’. Therefore, leaving them off paintings of nude bodies is subscribing to a bodily ideal that is simply not found in nature. In that case, why bother giving nudes nipples at all? Why not just go full Barbie and airbrush them out in the same way that vaginas and pubic hair were themselves removed in paintings such as ‘Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time’ by Bronzino.3

Despite the propensity of art historians and critics to plumb the symbolic depths of even the most unprepossessing artworks,4 I have been able to find almost nothing about this topic. The sole exception is a single Reddit art history thread titled ‘Why are women’s nipples depicted so small in classical art?’ where various theories are presented, ranging from the plausible to the preposterous. For example, one respondent helpfully suggests that it was probably cold in the studios of classical artists, causing shrinkage amongst female models. Another posits that the use of pale models was surely to blame, because areolae are less visible on pale skin.

Demonstrating a little more wit (or, at least, less ignorance of the fundamentals of female physiology5) another poster argues that artists would rarely have had the opportunity to study unclothed female bodies, so it’s hardly a surprise that their representations were inaccurate. However, while the use of males as stand-ins for female models was common during the Renaissance, there is evidence that at least some artists had begun to use nude female models.

Moreover, a few contemporaneous paintings of Venus have visible areolae (e.g., Titian’s ‘Venus with an Organist and Cupid’ and Tintoretto’s ‘Mars, Venus and Vulcan’), so they weren’t an entirely foreign concept, given that artists only had to look at male models – or, indeed, their own bodies – to observe them. Their absence on female nudes therefore seems to be more a case of areola prejudice than areola ignorance.

The most convincing explanation presented in the Reddit thread is that tiny, areola-less nipples represented refined tastes and self-control in much the way that small penises did in classical Greek and Roman sculptures. Thus, large genitals, breasts and nipples were considered animalistic and barbaric.

Supporting this theory is the fact that large, pendulous breasts had strongly negative connotations in the Western tradition. According to the art historian Rebecca Brienen, ‘witches, devils, and even the emblem for envy were known by their wrinkled, pendulous breasts with elongated nipples, which both advertised and denied their sexual desirability’.

Brienen observes that African women were often depicted with such breasts, presumably to symbolise their perceived animality, barbarism and promiscuity. For example, in the Dutch trader Pieter de Marees’ 1602 book Description and Historical Account of the Gold Kingdom of Guinea, he described elderly African women as having breasts like ‘old pig’s bladders’.

The fact that the nipple was not removed entirely from European art is presumably because it was (and remains) a highly eroticised part of the breast, as well as a key signifier of motherhood. However, as the historian Marilyn Yalom has discussed at length, the breast has powerful and contradictory cultural meanings: it symbolises nourishment and life, but simultaneously enticement and aggression. This, of course, is why breasts are ‘bazookas’ but also ‘snuggle pups’, ‘mother lodes’ but also ‘devil’s dumplings’, ‘jawbreakers’ but also ‘cream pies’, and ‘chest butts’ but also ‘lady lumps’.

Breasts also symbolically connect humans with other mammals (literally, given that Mammalia means ‘of the breast’), and women, in particular, with nature. To quote the anthropologist Sherry Ortner, ‘Her body and its functions, more involved more of the time with “species life”, seem to place her closer to nature, as opposed to men, whose physiology frees them more completely to the projects of culture’.

After all, women have ‘tits’, a term derived from the same root as ‘teat’: the generic term for the nipple of the mammary gland of a female mammal. Women’s breasts must thus be pert, lest they look too much like de Marees’ ‘old pig’s bladders’ or, indeed, ‘udders’ – as one Australian cosmetic surgery firm characterised breasts in a 2017 ad for its augmentation services (the ad was immediately banned by the Australian Advertising Standards Board6).

Pert, areola-less bosoms seem to have been the Renaissance response to these contradictory meanings, serving to tame the symbolic association of breasts with animality, barbarism and promiscuity and, not coincidentally, heightening their connotations of youth and purity, given that areola size naturally increases with age, pregnancy and ptosis – i.e., the effects of gravity. As the surgeons Webb and colleagues observe, in a statement as notable for its sheer obviousness as its undoubted accuracy, ‘the breasts most dominantly associated with sexuality are those that frequently belong to women with limited sexual experience’.

In fact, the reports of cosmetic surgeons make it abundantly clear that we remain just as obsessed with the breast-nipple complex as we were four hundred years ago. After all, nipples should only be in public view when exposed by a stripper rather than a mother breastfeeding her child – although in many American states, the former should cover them with pasties,7 unless she works in a commercial establishment where alcohol is served (your guess is as good as mine). And even nipple shields are not enough if she accidentally exposes a boob at the Super Bowl – as Janet Jackson discovered during Nipplegate.

While areolae are no longer completely erased, they are nevertheless expected to be delicate in size. They should, for instance, be smaller in diameter than an Oreo, lest the woman be accused of having ‘oreolas’. They should also be round rather than elliptical or uneven to avoid the accusation of ‘Franken-nipple’. Indeed, according to the authors of ‘Metrics of the aesthetically perfect breast’, the accepted standard areola diameter has been classically set at 38–45 mm. More recently, it has been proposed that the ideal areola-breast proportion is 1:3.4 – kind of like a golden ratio for breasts.8

Clearly then, the missing areolae in classical art is nothing more than a symptom of our longstanding cultural obsession with boobs. While the appearance of the ideal breasts might have changed over the centuries – from ‘lily white balls’ in the seventeenth century to ‘areola alps’ in the twenty-first – our fixation with mammaries has not. Breasts are never just breasts, but a primary site onto which conceptions of femininity are projected. In that respect, missing areolae are actually a flashing neon sign that you’re looking at a representation that does not exist in nature. And who knows? Maybe that was the intended message: ‘Look, admire, but don’t aspire, because these, my friend, are the love muffins of a goddess’.9

Related posts

To give credit where credit’s due, it was actually my husband who noticed the absence of areolae. I put this down to the fact that he was clearly inspecting the female nudes’ breasts far more attentively than me.

This pose is known as the Venus Pudica and implies modesty while simultaneously drawing attention to the exposed area, thus aiming to titillate* the viewer.

*Led astray by a scene in the 1982 movie Night Shift wherein Michael Keaton creatively explains the etymology of ‘prostitution’, I originally thought that ‘titillate’ was etymologically connected with ‘tit’. For the record, it actually comes from the Latin term titillare, ‘to tickle’, a word imitative of giggling.

Interestingly, the mons pubis is also known as the ‘Mound of Venus’, presumably because it features so prominently in depictions of the goddess. However, most give the impression of of Barbie doll-like flatness beyond the mons pubis itself.

Call me a philistine, but is the act of dripping paint on a canvas really a symbolic attempt to ‘free line not only from its function of representing objects in the world, but also from its task of describing or bounding shapes or figures, whether abstract or representational, on the surface of the canvas’.

For the record, nipples and areolae become more, not less, prominent in cold air, and areolae come in many sizes and colours – including on women with pale skin. The jury is still out on the effects of Albinism on nipple and areola colour, but I think we can safely assume there was not a glut of Renaissance models with the condition.

In response, the advertiser implied that a bunch of humourless feminazis had misrepresented their ‘light-hearted’ ad, because they merely wanted to let women know they could augment their breasts ‘if they wish to remediate for some of the effects of child-birth and breastfeeding’. Why would anyone possibly take offence to that?

The tasseled nipple coverings, not the delicious Cornish pastry.

True to form,* The Sun has recently determined that the owner of the best boobs in the world according to the golden ratio is Coronation Street alumna Michelle Keegan.

*The Sun pioneered the Page Three girl and pictures of scantily clad celebrities remain their bread and butter. They’re the kind of rag that covers Free the Nipple campaigns purely so they have an excuse to plaster boobs all over their front page.