When I was little, I was frequently called ‘Giggling Gertie’ because of my extreme ticklishness and tendency to fall into bouts of uncontrollable laughter.1 Basically, once I started laughing, I found it very difficult to stop. The problem was particularly acute in contexts where I wasn’t supposed to laugh. If I found something funny, I struggled not to laugh, even if – actually, especially if – laughter would have been highly inappropriate.

One of the best descriptions I have seen of this phenomenon can be found in the early noughties UK sitcom Coupling, where it is described as the ‘giggle loop’. In the words of the Welsh character Jeff:

‘Basically, it’s like a feedback loop. You’re somewhere quiet. There’s people. It’s a solemn occasion: a wedding. No! It’s a minute’s silence for someone who’s died… Suddenly, out of nowhere, a thought comes into your head: the worst thing I could possibly do during a minute’s silence is laugh. And as soon as you think that you almost do laugh – automatic reaction! – but you don’t. You control yourself; you’re fine. But then you think how terrible it would’ve been if you’d laughed out loud in the middle of a minute’s silence, so you nearly do it again, only this time it’s a bigger laugh’.

Unfortunately, this tendency has accompanied me into adulthood, although I struggle with it less now than I used to, primarily by employing the same technique I use for dealing with motion sickness: staring fixedly at an object and focusing on breathing until the desire to either vomit or laugh abates. But sometimes the urge to laugh in inappropriate contexts remains irrepressible.

I clearly remember the last few times I lost the battle. The most public incident occurred in 2004, when I was convening the anthropology seminar series at Macquarie University in Sydney: a weekly seminar where staff and students would gather to hear a speaker, mostly someone invited from outside the university. Significantly, the seminar was held in a small room set up in the manner of a boardroom; the speaker would sit at the front of a large table and present to students and colleagues clustered around it.

Halfway through the semester, a Chinese woman started to turn up to the series. No one knew who she was, but she always brought a mason jar that presumably contained some sort of tea, and she would unscrew the lid while watching the speaker intently – listening avidly to what they were saying as she sipped her tea. Probably, this would not have stood out except for the fact that it was her habit to sit right next to the presenter if the room was crowded, in a spot at the front of the seminar table that everyone else deemed off-limits on the grounds of proximity.

I’m not sure if it was a lack of familiarity with Australian seminar norms or eccentricity that caused her to repeatedly sit next to the speaker, but presenters generally found it deeply disconcerting. They would glance at her uncertainly at the outset, and then valiantly try to ignore her as they started their talk and she gazed at them intently and sipped her tea, scant inches from their face.

Anyway, one day the whole thing struck me as deeply funny. When the woman sat down next to the day’s speaker, started to unscrew her tea and stared at him intently, the urge to laugh came upon me. I tried to control myself, because there was no way to interpret my laughter as anything other than extremely rude and possibly racist, but every time I thought of speaker’s look of alarm, I wanted to laugh.

Despite the fact that the speaker was mid-sentence and I was officially convening the seminar, at a certain point I lost the battle. I rushed from the room, hoping that people assumed I was suffering from a latent attack of diarrhoea – anything that might explain my abrupt departure. Then, I went to the women’s toilets and laughed my head off for a good five minutes or so to get it out of my system. Thankfully, no one came into the toilets, because I looked and sounded insane. Once I felt like I’d got myself under control, I wiped my eyes and returned to the seminar, hoping my absence hadn’t been too noticeable.

There’ve been other incidents since then, including an experience at a pretentious Michelin-starred restaurant in Ireland in 2018 on my birthday, where the sommelier’s description of the wine being served with each course set me off. After he described a wine as having a palette like ‘a 1920s starlet: she’s bold; she wears red lipstick’, I lost it completely.2 From that point, every time he described a wine, I sat there, shoulders shaking, making snuffling noises. It was extremely rude and my husband was mortified, but I couldn’t make myself stop.

There is nothing like laughing in front of people who are either mortified, horrified or utterly bemused by it to realise that laughter is a rather strange thing. Ideally, laughter is something we share. According to the anthropological linguist Munro Edmonson, this makes it fundamentally different from other expressions like cries of grief and pain.3 Laughter is sociable; it ideally invites a similar response. Indeed, it has contagious qualities: when we hear someone laugh, we often laugh, or at least smile, ourselves. In essence, laughter itself has been shown to evoke laughter.

But laughter when you’re the only one doing it? Well, that smacks of insanity – or, at least, it reveals that laughter is not just about humour, but is something rather more complicated. As the cultural studies scholar Fran McDonald shows in her analysis of the reaction to Natalie Portman’s laugh in her acceptance speech following her Oscar win for Black Swan, which quickly became the subject of endless looped videos, ‘laughter without humor appears to render us mechanical, terrifying, monstrous’.

According to Edmonson, the central feature of laughter is aspiration: we release a forceful puff of air as we laugh. But laughter is also characterised by repetition. In fact, given the extraordinary variability in the sounds people make when they laugh, it’s often repetition that identifies the sound as laughter. This is why laughter is often conventionalised in writing as ‘he-he’, ‘ha-ha’ or, at least if you’re Santa Claus, ‘ho-ho-ho’. Notably, this feature isn’t exclusive to English representations. Edmonson observes that laughter is conventionalised in Russian as xe, xe, xe; in Tzotzil – a Mayan language spoken in Mexico – it’s ‘eh ‘eh ‘eh.

Consider the following clip of a French talk show focusing on people with unusual laughs. Although non-French speakers have little clue as to what they are talking about, and the guests produce some truly startling honks, snorts and shrieks, it’s the repetition of the sounds (as well, obviously, as the expressions on the guests’ faces) that signals laughter.4

This distinctive acoustic and rhythmic structure makes laughter universally recognisable. Having studied laughter in numerous societies, Edmonson concludes that it’s not culturally coded. Recognisable laughter is evident in babies from two months old and it also has the same pattern in deaf and mute children.

We don’t fully understand why humans make this sound when we laugh. As Darwin observed, ‘why the sounds which man utters when he is pleased have the peculiar reiterated character of laughter we do not know’. However, the response is not unique to humans – great apes respond to being tickled in much the same way that humans do.

Of course, because chimps, bonobos, etc., have a different vocal apparatus to humans, it sounds more like a dog panting or a person having an asthma attack or energetic sex,5 but it has the same ‘peculiar reiterated character’ that Darwin highlighted. For such reasons, Marina Ross and colleagues argue that ‘At a minimum, one can conclude that it is appropriate to consider ‘‘laughter’’ to be a cross-species phenomenon’.

Yet, while laughter is evident in the play of other primates, they don’t display a sense of humour – or, at least one that is recognisable to humans. As the evolutionary psychologist Robert Provine notes, ‘there is no evidence that they respond to apparently humorous behavior, their own or that of others, with laughter’. For instance, if a chimpanzee slips on a banana, the other chimps don’t break out in laughter in the way that humans – or, at least the millions responsible for the success of America’s Funniest Home Videos6 – do. Giving meaning to laughter, well, that seems to be something distinctively human.

Generally, we assume that we laugh because we find things humorous. According to Provine, we treat it either as a voluntary choice made to reward the behaviour of others, or a response to something naturally ‘funny’. But laughter occurs for all sorts of reasons that have nothing to do with humour. For instance, because we laugh when we’re tickled, we often tickle children on the premise that tickling is ‘fun’. But few people actually enjoy being tickled7 and it has historically been used a form of torture. To quote the anthropologist Lidia Dina Sciama, ‘there can be humour without laughter, and conversely much laughter can be quite humourless.’

Key to laughter is its involuntariness. Provine notes that while some laughter is voluntary, much of it is outside our conscious control. Spontaneous, emotive laughter therefore suggests that it has escaped the bounds of restraint, which may be one reason why we somewhat derisively compare unalloyed laughter with the cries of animals. As Edmonson observes, we describe human laughs as ‘braying’, we talk of people ‘howling’ with laughter, ‘hooting’ in delight, ‘snorting’ their amusement, etc.

As I have previously discussed at length, the European obsession with ‘culture’ and civility means that natural human attributes like snot, farts – and even areolae and nipples – have long caused us considerable anxiety. This also explains why we have an ambivalent attitude towards laughter, especially laughter that seems to be outside our conscious control. For instance, in an 1860 etiquette guide titled Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness: A Complete Hand Book for the Use of the Lady in Polite Society readers are counselled to moderate their laughter during a dinner party so that it’s neither too loud nor too soft: ‘To laugh in a suppressed way, has the appearance of laughing at those around you, and a loud, boisterous laugh is always unlady-like’.

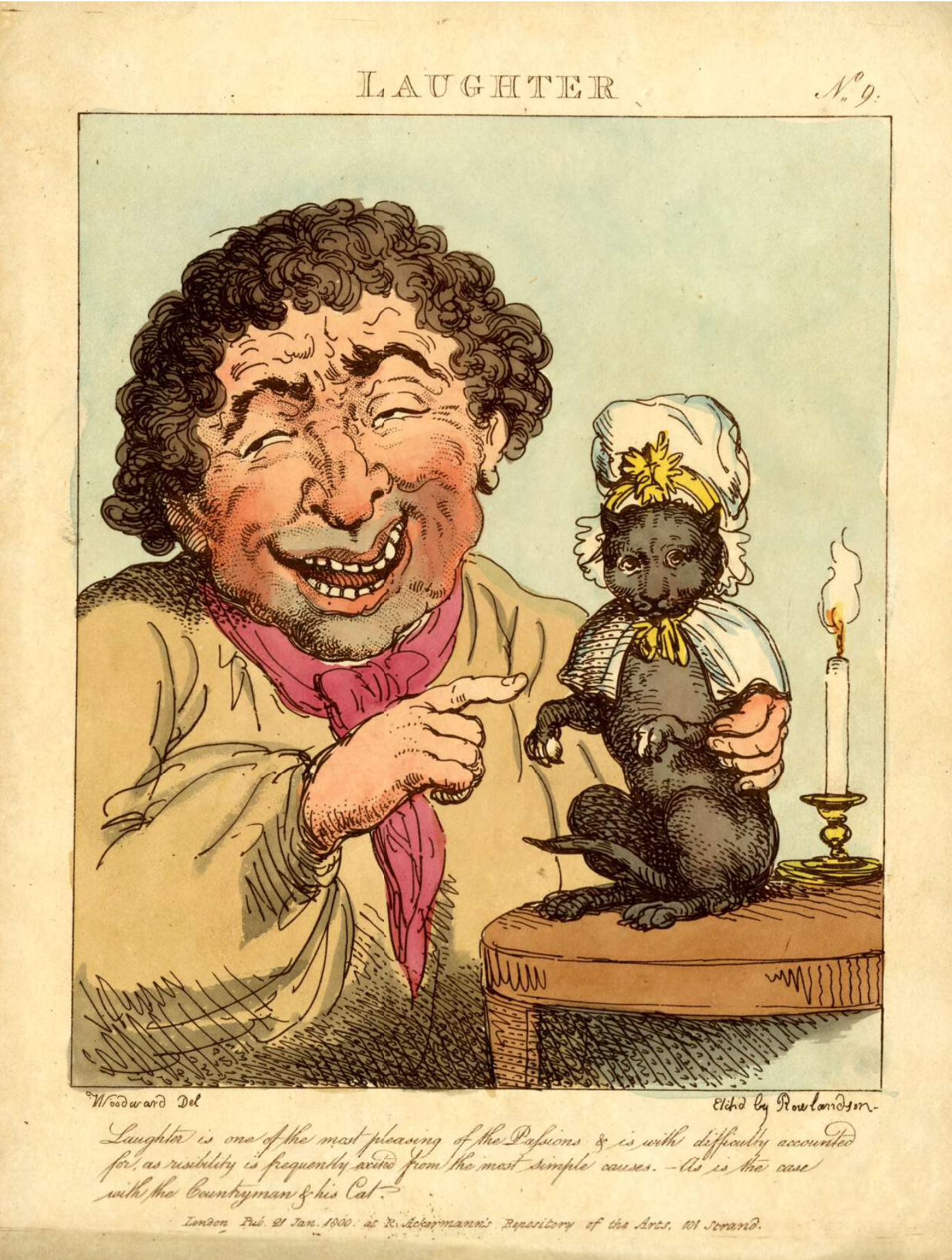

These sort of judgements reveal an attempt to try and draw laughter into the realm of taste – something evident in the fact that we talk about people having either a ‘sophisticated’ or ‘childish’ sense of humour. The nineteenth century depiction of laughter at the beginning of this article illustrates the same conflation. The caption reads, ‘Laughter is one of the most pleasing of the Passions and is with difficulty accounted for, as risibility is frequently excited from the most simple causes – as is the case with the Countryman and his Cat’. The implication of the cartoon is that there is no accounting for taste, because country bumpkins laugh at such ‘simple’ things.8

However, the fact is that is that we can’t necessarily control what we laugh at. ‘This is unbelievably stupid’, I used to declare whenever my husband watched the TV show Wipeout, where contestants completed ridiculous obstacle courses in the hopes of winning $10,000 and audiences tuned in to see them repeatedly being hit by objects, repeatedly falling off objects and repeatedly falling onto objects. But I would laugh anyway, because I simply couldn’t help myself.

Fran McDonald highlights this disruptive quality of laughter and the way it upsets our notion of a stable, coherent self. Moreover, unrestrained laughter doesn’t just signify a lack of personal control; it can be politically dangerous as well – as the art historian Joseph Butwin notes in his discussion of ‘seditious laughter’. Shared, sanctioned laughter might bring us together, but unsanctioned laughter reveals the cracks; as Fran McDonald notes, we call it ‘cracking up’ for a reason. Likewise, we ‘burst’ with laughter.

In the end, laughter remains a curious thing. We might be unique in attributing meaning to our laughter, but we are far from the only species to laugh. In fact, of all the human expressions it’s probably the one that’s simultaneously the most social and the most disruptive of social edifices and rules. Laugh and the world laughs with you, but laugh too loud or too long, or – even worse – laugh when you’re not supposed to, and you’ll quickly find that laughter isn’t quite so funny after all.

Related posts

For a time, I was also called ‘Instant Replay’ because of my tendency to repeat everything my older sister said – not out of mockery, mind you, but out of adoration. For the first five or so years of my life, I was my sister’s devoted acolyte.

In fairness, can you blame me? The sheer level of posturing that wine produces is unrivalled by any other beverage or food. One of the most memorable lines in the movie Spy is when Melissa McCarthy’s character tries to order wine at a posh European restaurant and describes her preference for ‘noisy’ reds with a ‘barky finish’ and whites ‘with the grit of a hummus’. For the record, Spy may not be the wittiest movie I’ve ever seen, but it is the one that makes me laugh the most while watching it. To quote the Pulitzer-prize winning film critic Wesley Morris, ‘At comedies, I usually keep a tally of the number of times I laugh. I lost track at Paul Feig’s Spy. Laughing at this movie became a form of exercise. You don’t need crunches when you’ve got this’.

Unless, of course, you’re a child. I’m always impressed by how quickly infants learn to perform pain for maximum effect. You see it very clearly when a child falls over, hasn’t really hurt himself, but then starts wailing dramatically as soon as his parent rushes over to see if he’s okay. Actually, substitute ‘referee’ for parent, and you see basically the same phenomenon in professional footballers.

Personally, I can’t watch the clip without laughing myself, even though I have no idea what they’re talking about. This points to the aforementioned contagious quality of laughter. Hearing others laugh at their laugh seems to make the guests laugh even harder, producing a feedback loop in which the guests laugh, the audience laugh at the guests’ laughs, which causes the guests to laugh harder, which causes the audience to laugh harder. This suggests that laughter potentially produces a different kind of laugh loop in which it’s the sound of laughter (as much as the desire to suppress inappropriate guffaws) that produces more laughter. You can blame this insight for the invention of canned laughter as studios realised that the sound of laughter made their shows seem funnier to audiences, while also giving them a degree of control over when people laughed.

At least, according to the evolutionary psychologist Robert Provine, who played audio recordings of chimps laughing in two college classes. Some students also assumed they were listening to the sounds of DIY activities like sawing or sanding, which goes to show how much we rely on personal context for interpreting sounds. For instance, I recently stayed in the country with some friends and there were numerous cows on the property, which we only discovered when they milled around the house mooing at 5am the next morning. The friend who lives in central London initially thought she had been awoken by the sound of drilling.

The most successful genre of clips on the show is arguably ‘humorous accidents’. Of course, they’re not particularly funny for the poor bastards being caught on film, but the rest of us tend to find them hilarious (even if we won’t admit it). Arguably, the genre of humour that is most effective in transcending cultural differences is physical comedy, which is why some screenwriters predict that it will become increasingly prominent in Hollywood comedies, given that films now need to appeal to global audiences in order to produce reliable returns. As far as I can tell, the future of Hollywood is basically Marvel movies and slapstick comedies.

It turns out that tickle torture is a sex thing,* which I learned after Google took me down some dark paths. Anyway, suffice to say, a minority of people enjoy being subject to tickle torture.

*Which begs the question, is there anything that isn’t?

For the record, I have a similarly unsophisticated sense of humour* because I have an image of my beloved (now deceased) cat, Spike, that is virtually identical to the cat in the picture and, yes, I laughed my head off when I took the photo – my cat was less amused.

*If you’ve been reading this Substack for a while, I suspect you knew that already.

I just discovered this posting through its republication as a Pocket article. I wanted to share one further facet that may interest Kirsten Bell. More than ten years ago I was involved in a protracted (February to October) and confrontational picket line to protest the opening of an aggressively gentrifying restaurant. Somehow by instinct I came to the idea of raucously laughing at poshy customers who insisted on crossing the line. I could sense that doing that was distressing them more than shouting did.