A meditation on eyebrows

27 July 2023: When I published this piece, little did I know that Sinéad O’Connor would die three days later. Rest in Peace, Sinéad. As the tributes start pouring in, I hope that her magnificent, anti-establishment eyebrows get a mention, because in their own way they were just as subversive as her shorn hair.

I have recently had cause to ponder the significance of eyebrows. This is primarily because my sister, who is currently undergoing chemotherapy, has begun to shed hair at a rapid rate. While she is not particularly fazed by the loss of her head hair, and has now had what remains of it buzzed off, we were recently talking about the loss of her eyebrows and eyelashes, and the resulting difference to her appearance.

As my sister is well aware, what makes a cancer patient look like a cancer patient is not the largely bald head that various types of chemo produce, but the accompanying loss of eyebrows and eyelashes.1 One look at Sinéad O’Connor singing Nothing Compares 2 U, and her magnificent brows and lashes make it clear that she is choosing to rock a buzzcut.2 When someone is lacking eyebrows, on the other hand, you can’t quite put your finger on how they look different, but you know something is off about their appearance.3

Pretty early on, I realised how important eyebrows were, primarily because I didn’t have any. As an infant, my hair, eyelashes and eyebrows were so pale, thin and fine that I looked like I was undergoing chemo myself.4 Although my hair darkened as I got older, even as a ten year old, I still had no visible eyelashes or eyebrows to speak of (as the picture at the bottom of my Barbie post attests).

From about the age of 15, I started dyeing my eyebrows in a bid to make them more visible.5 This was partly because I’d gone to a lot of effort to train myself to raise one eyebrow,6 which I figured was largely for nought if people couldn’t see the results of my endeavours (imagine Dr Spock crossed with Tilda Swinton and you’ll get close to the effect). Tyra Banks can talk all she wants about smizing, but Dr Spock had already taught me that real emotion resides not in the eyes, but the eyebrows.

One only needs to look at the actor Colin Farrell to understand the power of expressive eyebrows. As a recent GQ article titled ‘Colin Farrell’s eyebrows should win an Oscar each for Banshees of Inisherin’ puts it, ‘If the eyes are the window to the soul, the eyebrows are the curtains which really tie the room together’. Unquestionably, it’s Farrell’s ‘veritable ballet of eyebrow theatrics’, that are the clearest barometer of the character Pádraic’s emotional state. In this case, the ‘eyebrows’, rather than the ‘ayes’, have it (sorry).

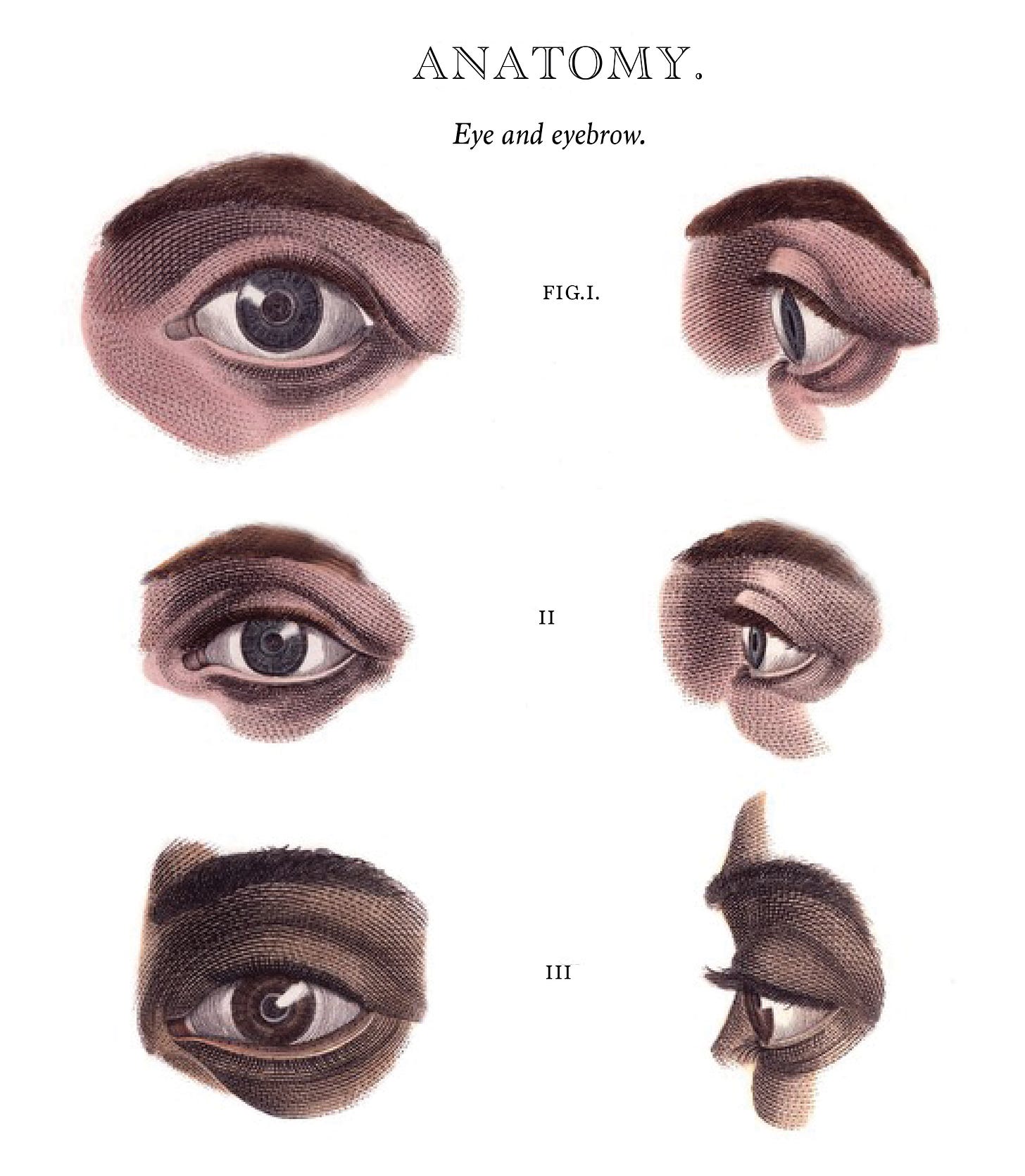

Anthropologists have long been aware of the power of eyebrows in human non-verbal communication. As the biological anthropologists Karen Schmidt and Jeffrey Cohn note, six basic expression categories have been shown to be recognisable across cultures: disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise and anger. As the image below illustrates, the eyebrows are arguably the single most reliable indicator of an emotional state – cover the mouth in the images and you’ll see what I mean. Moreover, greeting someone is typically accompanied by a brief eyebrow flash: a gesture that is universally used and recognised.

Although the longstanding view is that eyebrows evolved to protect our eyes and keep them clear of sweat, dirt, dust and water, Godinho and colleagues argue that the key to the evolution of eyebrows in modern humans is their ability to display subtle signalling behaviours. As they observe, our highly mobile eyebrows are distinctive to modern humans; Neanderthals, in contrast, had a much more pronounced brow ridge.

Neanderthals’ brow ridge is generally understood to be either the result of the spatial relationship between their eye sockets and brain case or biting mechanics caused by the requirements of chewing tough food (or both). However, Godinho and colleagues dispute these theories, suggesting that structural factors don’t adequately explain the prominence of Neanderthals’ brow ridge.

In their view, sociality and social communication must be considered in relation to both the larger-than-needed brow ridge of archaic humans and the reduced brow ridges and more vertical forehead of modern humans. While a stronger brow ridge looks more intimidating, acting as a sort of permanent social signal of dominance and aggression, the highly mobile eyebrows of humans can be used to express a wide range of subtle emotions, which, Godinho and colleagues suggest, would have played an invaluable role in our survival.

Whether you buy their arguments or not, eyebrows are clearly a critical component of human communication. As the evolutionary psychologist Rachel Jack has observed, the expressive value of eyebrows made them ‘strong candidates for evolution to pick them up as social signallers’. This is why the current preoccupation with freezing them into immobility is so intriguing from an anthropological standpoint. In effect, people are sacrificing their ability to communicate non-verbally in order to approximate a more youthful – or, at least, less lined – appearance.

Now, Allergan, the makers of Botox, will tell you that the ability to freeze facial muscles is one of the botulinum toxin’s many benefits. Thanks, in large part, to the facial feedback hypothesis, which suggests that our facial expressions affect our emotions as well as vice versa, Allergan have started clinical trials on the use of Botox to treat depression (they’re now in Phase III trials, so not far from the licensing stage). If you can’t look depressed, the logic goes, then you won’t feel depressed.7

Although it’s a rare day when the Guardian and the Daily Mail agree on anything, the press response to the initial trial results has been uniformly positive. For example, Guardian columnist Zoe Williams approvingly quotes a plastic surgeon stating, ‘When you can’t furrow your brow or show the emotions of concern or fear or panic, there is likely a calming effect on the nerve pathways that feed back to your brain that then allow you to actually not feel that emotion quite as much’. She then marvels at the fact that, post-Botox, she now ‘genuinely can’t frown’.

The problem, of course, is that as least one Daily Mail reader intuited in response to an article titled ‘Botox “may banish the blues”’, the toxin might stop you frowning, but it will ‘also eliminate all your effect’.8 Indeed, the psychologist Michael B. Lewis has found that Botox on crow’s feet (a.k.a. ‘laugh’ lines) and the frown lines associated with sexual excitement9 increased depression scores in female test subjects, and was also associated with reduced sexual function.

If Godinho and colleagues are right that our eyebrows evolved as a social signalling cue, then our eyebrows aren’t really about us at all, but other people. Regardless of whether freezing our face flattens our own emotions, it unquestionably inhibits other people’s ability to make sense of our expressions (and, evidence suggests, our attempts to make sense of other people’s expressions in turn). Anyone who’s ever watched a heavily Botoxed actor trying to emote fear will have experienced the jarring sensation of being thrust out of the story, as your brain tries to process what you’re seeing. You know the actor is supposed to be scared shitless, but they just look constipated instead.10

So are we destined for a future in which we’re all effectively living in Madame Tussaud’s, except with live people? Or will we become so expert in reading micro facial expressions that we all make Dr Cal Lightman from Lie to Me look like a rank amateur? Or perhaps our eyebrows are destined to become a vestigial body marking whose purpose is purely ornamental. Only time will tell, but one thing’s for sure: without the muscles that animate them, eyebrows no longer have a purpose. Unless, that is, eyebrow emojis turn out to be the next step in the evolution of facial expressions themselves, at which point I think I can safely say that our species, like the Neanderthals before us, is doomed to extinction.

Related posts

This is where cancer movies get it wrong. While most actors are willing to remove their hair for a role, verisimilitude clearly ends at plucking their eyebrows and eyelashes – although they might be convinced if an Oscar is in contention and they’re ‘acting ugly’ in the hopes of winning one.* For example, in the definitive cancer flick of my generation: the Julia Roberts vehicle Dying Young (not, for the record, ever a viable contender for an Oscar), Campbell Scott’s character spends much of the movie with a bald head, but with those full eyebrows and eyelashes it was clear he was faking it.

*As soon as I saw Charlize Theron’s eyebrows in Monster, I knew that she was going to win an Academy Award for the role.

It’s impossible to emphasise enough just how much of a rebel Sinéad was. Everyone always focuses on her buzzcut and that time she tore up the picture of Pope John Paul II, but what they should really have been talking about were her anti-establishment eyebrows. So full! So natural! It’s difficult to convey how counter they were to nineties brows, when the super-thin, over-plucked brow reached dizzying cultural heights not seen since the 1930s. Unfortunately, the beauty pundits are telling us that the skinny nineties brow is back in, but we wouldn’t be stupid enough to go there again. Right?

The clearest illustration I have seen of this is an incident involving my husband. Not long after we met, he was the subject of a drunken prank where his eyebrows were shaved off by his mates (a term I clearly use loosely*) while he slept. As his eyebrows are normally rather prominent, he looked startlingly different – Lurch from The Addams Family was the most frequent descriptor. But while everyone did a double-take when we saw him, none of us could figure out exactly why he looked so different.

*Especially since this was not the first time it had happened – although in the prior incident they just shaved off one eyebrow, with Andrew resorting to covering the other one with a bandaid in the hopes of hiding its absence. How long does it take an eyebrow to grow back? Six weeks.

There’s a reason why Gerber babies always have hair and visible eyebrows and lashes. Take that away and what you get is basically chemo-baby: a baby that is distinctly less cute and distinctly more ‘ill’ in appearance. Suddenly those bright eyes merely look feverish, and that mouth appears to be about to start wailing, because we don’t have the eyebrows to tell us to interpret it as the prelude to a smile.

Although I stopped after an unfortunate dyeing incident in which I slathered dye all over my brows and then forgot about it. Two hours later, after being startled by my appearance in the mirror, I finally remembered to remove it, but it was too late. My eyebrows and the surrounding skin had been stained to Groucho Marx-like proportions. In a vain effort to remove the dye, I ended up scrubbing the skin surrounding my eyebrows off, so for the next few days I looked like Groucho Marx after a crying jag.

This largely consisted of me sitting in front of the mirror on my parents’ wardrobe for hours on end and saying to my left eyebrow, ‘lift, damnit, lift!’. And then, one day, it did.

I could be wrong, but I suspect that some day we’ll put this bit of wisdom in the same category as ‘sneezing is a form of mini-orgasm’. Indeed, its logic is equally dubious and virtually identical. (‘See, the expression you make when you sneeze looks like the expression you make when you orgasm and you clench the same muscles, so a sneeze and an orgasm are basically the same thing!’)

On this topic, the Daily Mail readers turn out to be a fount of good sense. ‘That must be an ad for Botox’, said another.

How do we know people consistently frown just before they orgasm? Because Master and Johnson (popularised in the TV show Masters of Sex) studied behaviour during 10,000 sexual interactions. Oh, and then this mob studied the recordings of 100 volunteers who’d filmed their own orgasms and uploaded them to the internet. For the record, they found that facial expressions just prior to orgasm are virtually indistinguishable from what our faces look like after we accidentally hit our finger with a hammer.

Constipation produces your classic flat eyebrow look; the effort of laying uncooperative cable manifests itself primarily in squinted eyes and a clenched jaw. Being scared shitless, on the other hand, is all about the eyebrows, which are raised in the centre, but droop down at the ends, like they’ve wilted half way through committing to a pose.