This piece relies on some familiarity with my earlier post on different conceptions of politeness so that one is best read before this.

When I first moved to Canada in 2006, my impression was that Canadians were more culturally similar to Australians than Americans. We were both small populations in large countries with harsh climates and huge stretches of relatively inhospitable land, and we had both been forged by our ties to Great Britain – and had the Commonwealth membership to prove it. Unlike my earlier experience of living in the USA, I also didn’t have to constantly explain Australian idioms,1 so I felt right at home.

There were, of course, differences as well. Some, such as the existence of French-speaking Canada and its influence on national politics, were obvious. But others took more time to put my finger on and revealed themselves mostly via the whingeing of fellow Australian expats. For example, a universal complaint amongst Aussies of my acquaintance was that Vancouverites were polite but not friendly; there was a degree of reserve in interactions that they found unexpected and frustrating.2

This is certainly not a view that one hears frequently voiced about Canadians – quite the opposite, in fact. Canadians are widely perceived to be both polite and friendly. ‘Nice’ is also a frequently used adjective, along with its sibling, ‘non-aggressive’ – readers may recall the 2000 study on national stereotypes by the social psychologist Francis McAndrew and his colleagues in which this was the cross-cultural consensus on Canadians, although no one could agree on which country was most polite.

However, my suspicion is that if the survey was replicated today, Canada would come out as the most polite of the five English-speaking countries included in the study. This is because the stereotype of the polite Canadian is now firmly entrenched in the global imagination, from Canadian TV shows to American films like Anchorman II – as the following scene from the film illustrates.3

Based on Brown and Levinson’s typology of positive and negative politeness, the emphasis on the nice, apologetic Canadian suggests that the Canuck form of politeness is primarily negative. Indeed, this is precisely what the communications scholar Aisha Mansaray has found: Canadian English speakers use polite linguistic markers in order to avoid imposition and conflicts.

It also makes sense of the complaints of Australian expats when I lived in Vancouver. As I have previously outlined, Australian politeness generally takes a positive form; according to Mansaray, it’s characterised by speech markers that convey friendliness and solidarity. Therefore, Australians are particularly attuned to the differences between positive and negative politeness, no doubt exacerbated by their expectation that the Canadian form will be akin to the Australian one, given the other cultural similarities they observe.

On the face of it, the more reserved and apologetic form that politeness takes in Canada connects it with the English form, suggesting that it’s an artefact of the country’s origins as a (mostly) British colony. But as a naturalised Canadian who now lives in the UK, I think this is only half the story. While social etiquette appears similar between the two countries, there are nevertheless significant differences between them.

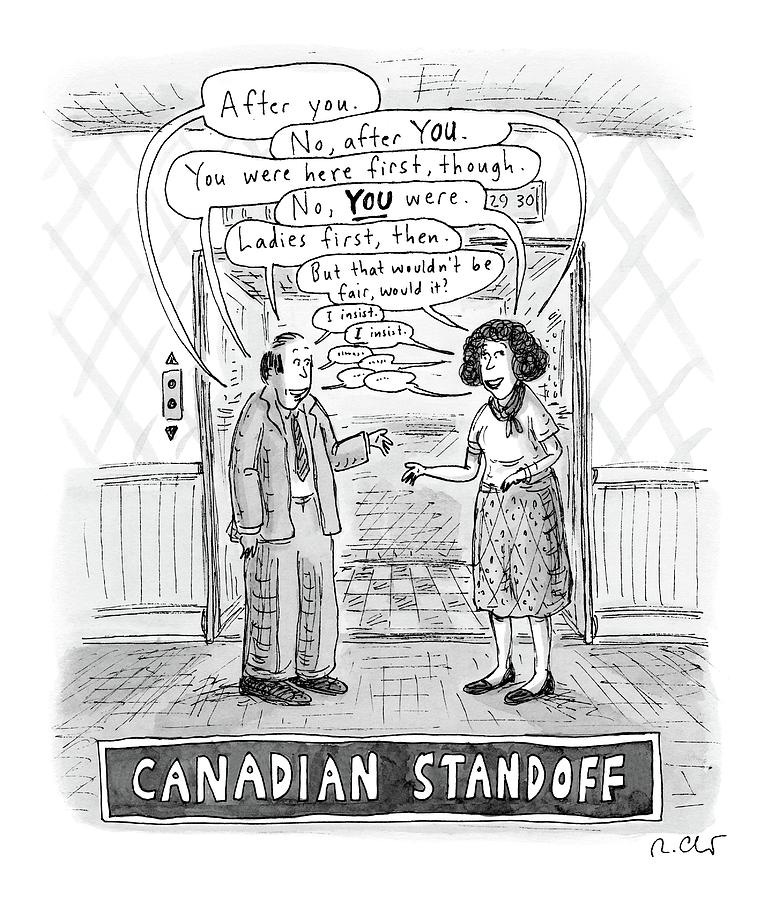

First, Canadian politeness is more egalitarian than its English counterpart. In my experience, Canadians are much more likely to thank people in service positions than English people are – especially bus drivers. Second, politeness isn’t just about linguistic etiquette, but polite actions. For example, the Canadian standoff really is a thing, especially when contemplating seconds during a shared meal. It’s also standard to remove your shoes when you enter someone’s home. Although typically treated as an artefact of the snowy and muddy Canadian winters, my suspicion is that the practice evolved because some homes had a shoes-off policy and others didn’t, and rather than put hosts in the awkward position of asking guests to remove their shoes,4 Canadians started taking them off upon arrival as a matter of course.

This politeness also extends from drivers to pedestrians. In Australia, if you try to walk across a road on anything other than a zebra crossing, you will be honked at and the driver will generally yell a variant of ‘Get off the road, fuckwit’.5 In the UK, drivers might let you cross if the light’s gone red and they’ll be stopping shortly anyway, but that’s as far as it goes. Conversely, in Canada, drivers will actively stop to allow you to cross the road, even if they’re going 50km per hour and you’ve merely paused at the edge, not even sure you want to cross.6

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, while Canadians, like the English, say ‘sorry’ all the time, they use the expression in a somewhat different way. Kate Fox argues that ‘sorry’ in an English context is a reflexive action that occurs whenever there is ‘any intrusion, impingement or imposition of any kind, however minimal or innocuous’. In Canada, ‘sorry’ is similarly reflexive; as the Canadian writer Emily Keeler observes, ‘sorry’ is an essentially meaningless courtesy rather than an admission of guilt. However, it is also a means of dodging conflict in situations in which you feel you are in the right.

For example, this is how Keeler describes a close encounter with a bus while she was riding her bike:

I could literally feel the whoosh of air as the truck was going by. He rolled down his window — probably to yell something like, ‘Sorry! I didn’t see you!’ — but, before he even had the chance I was already screaming, ‘SORRY!’ at the top of my lungs. I screamed ‘sorry’ even though I was incredibly angry.

Later in the essay, she elaborates on this point, noting, ‘Sometimes we say “sorry” and mean something more like: “I’m especially sorry to encounter so much human idiocy in you, a person who I am not actually inclined to aggravate right now”’. Although she doesn’t develop the point explicitly, she is basically suggesting that there is an aggressive dimension to Canadian ‘sorrys’.

This meaning becomes especially pronounced in a parody of Justin Bieber’s song ‘Sorry’ from the Canadian sketch comedy show This Hour Has 22 Minutes. If you watch it, you’ll notice that virtually all of the instances when Mark Critch says ‘sorry’ occur when he is aggrieved by someone else’s actions: they’ve given him the wrong order, they’ve spilled coffee on him, they’ve stolen his seat, etc. In effect, there is a passive-aggressive dimension to his apologies that I think is entirely missing from its reflexive English form.

This speaks to perhaps the most significant dimension of politeness in Canada that distinguishes it from its English counterpart: the American influence on conceptions of Canadian identity and the role that politeness plays within it. In much the same way that Australian national identity was forged in contrast to ‘Britishness’, Canadian identity has been forged in relation to ‘Americanness’.

The political scientist Gregory Millard and his colleagues observe that the distinction between Canadian diffidence and American brashness is fundamental to Canadian national identity (at least in English-speaking Canada). As I have previously noted, in their 2000 study on national stereotypes, McAndrew and his colleagues found that Canadians were wont to characterise Americans in a very negative light, perceiving them as particularly selfish, close-minded, patriotic, impolite, unfriendly and aggressive.7

In fact, there is some evidence to suggest that Canadians are more polite than Americans. For instance, after analysing millions of tweets, the Canadian linguist Bryor Snefjella and his colleagues found that Canadian tweets were noticeably warmer and more positive in tone than American ones, which included more swear words, expletives and racial slurs. On the basis of their research, the authors tentatively conclude that ‘national character stereotypes may be partially grounded in the collective linguistic behaviour of nations’.

Regardless of whether the stereotype has a basis in reality, Millard and colleagues’ work suggests that Canadians’ view of themselves as ‘retiring, unassertive, and diffident’ in comparison to their neighbours in the south has become fundamental to their nationalism. This inflects Canadian politeness in a particular way, because it’s entwined with this assertion of cultural difference from Americans. Put differently, Canadian politeness doesn’t mimic the English; rather, in its emphasis on diffidence it’s antithetical to the American form (which is stereotyped as brash and over-friendly). In consequence, Canadian politeness is both more self-conscious and less self-effacing than the English variant.

Millard and colleagues go on to argue that because Canadian national identity is effectively the mirror image of American identity, there is, in effect, a ‘loudness’ to Canadian assertions of their quietness – an attribute they suggest is evident in everything from the tendency of Canadian backpackers to plaster maple leafs on their rucksacks to the popular 2000 Molson Canadian beer ad titled ‘The Rant’. In their words, ‘Canadians are now, in effect, shouting about how quiet they are – frequently in paradoxical contrast to the “loud American”’.8

So, in contrast to love, which means never having to say you’re sorry (at least, according to Love Story), being Canadian means always having to say you’re sorry. But ‘sorry’ isn’t always an apology. Instead, picture Otto, the American in A Fish Called Wanda, screaming ‘arsehole!’ to everyone he cuts off in traffic, and you’ll be much closer to the truth, because while ‘sorry’ might mean ‘I apologise’, it can also mean ‘You’re an arsehole, but I’m simply too Canadian to say so’.

Related posts

Mostly because those idioms were actually British rather than Australian in origin, and were also used by Canadians – except for ‘No worries’, which has travelled far and wide across the English-speaking world but is definitely ours.

I think this is less true in the Prairies and the Maritime provinces. In fact, there appears to be a rural/urban divide in terms of perceptions of positive/negative politeness that transcends national stereotypes. Whether you live in the USA, Australia, Canada or the UK, you will hear people regularly complaining that the inhabitants of cities like New York, Melbourne, Vancouver or London are unfriendly – as this satiric comedy sketch about a Northerner in London nicely illustrates. As I mentioned in my earlier piece on politeness, there is massive variability within countries, which means that discussions of positive and negative politeness can only really occur at the level of crude cultural typologies. Still, while a deeply unfashionable topic amongst anthropologists, as Francis McAndrew and his colleagues observe, ‘Although stereotypes are often dismissed as illogical and factually incorrect – and as gross exaggerations of trivial group differences – the data do not support those assessments’. Also, nationalism, by definition, is about asserting a common identity that’s grounded in a sense of cultural difference, so you won’t get very far in understanding it if you refuse to take cultural stereotypes seriously.

I find this scene hilarious on several levels, not just for the passive-aggressive ‘sorrys’ constantly yelled out by Jim Carrey (a Canadian, for the record) and Marion Cotillard, but also for the passive-aggressive relationship between them, which articulates as well as anything I’ve seen the actual relationship between Quebec and the rest of Canada. At least in western Canada, there is a sort of sibling dynamic with Quebec, insofar as the latter is perceived as spoilt, bratty and prone to tantrums,* but also has a cool, rebellious streak you’re secretly jealous of.

*You know, the kind where your sibling dramatically declares that they are running away from home but then doesn’t and, to add insult to injury, acts like you should be eternally grateful that they continue to grace you with their presence, although you were sort of looking forward to finally having your own bedroom.

I speak from personal experience, having become Canadian enough to implement the practice in London. Unfortunately, this causes complications when we have Brits over, who never think to remove their shoes, thus leading a degree of mutual consternation when we ask guests to take them off.*

*Something a ‘real’ Canadian would probably never do.

All that Australian friendliness disappears as soon as people get behind the wheel of a car. Good luck if you expect people to let you in when traffic’s backed up! This YouTube clip is a perfect illustration of what supermarkets in Australia would be like if people behaved at the grocery store in the same way as they drive their cars.

I’ve never experienced anything like it anywhere else in the world. The first couple of times someone stopped their car, I was so taken back I felt obliged to cross the road, even though I’d merely paused to get my bearings. Of course, by the time I moved to London, I was so used to people stopping for me that I almost got killed on several occasions by stepping onto busy roads – although the fact that I was constantly looking for traffic in the wrong direction also probably had something to do with it.

Interestingly, Americans’ stereotypes about themselves largely cohered with the views of Canadians. So striking was the concordance between Canadian and American stereotypes that the study’s authors concluded that ‘given the agreement of the Americans with the Canadian stereotype, we cannot rule out the possibility that Americans, as a group, are simply more unpleasant people than Canadians’. Ouch!

Naturally, this made me think of the South Park episode on Harry and Megan’s ‘World-Wide Privacy Tour’, although instead of shouting about how quiet they are, they are constantly demanding privacy while seeking the public spotlight. In the episode they are, of course, the Prince and Princess of Canada. Since virtually the inception of the show, Canada has served as a foil for representations of Americanness, in ways that both invert Canadian stereotypes (they are obsessed with toilet humour) and reinforce them (they love maple syrup, say ‘aboot’ a lot, and are frequently the target of American aggression – who can forget ‘Blame Canada’). Oh, and unlike Americans, Canadians are always badly drawn, with Pac-Man-like heads.

Herewith two oldish items on the topic of “Canadian niceness”. I am sure there are many more, including your thoughts and contributions, of course.

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-march-31-2015-1.3016006/canadians-the-nicest-people-in-the-world-says-bbc-but-are-we-1.3016015

http://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2016/01/08/canadians-more-polite-on-twitter-than-americans-study-says.html