On not using headphones on transit

This post is dedicated to Ink.Readsalot, who first got me thinking about this topic in an online discussion of cultural quirks.

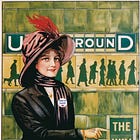

As anyone who takes public transport regularly will be aware, over the past few years, it has become much more commonplace for people to use their mobile phones without headphones. On any given train or bus ride in London, the chances are high that you will be forcibly exposed to someone else’s phone conversations and Zoom meetings, or their taste in music, film, TV shows and social media.

For example, yesterday on the tube, I sat next to a young girl watching a cartoon on a smart phone without headphones. Still, the volume was markedly lower than the guy I sat next to last week, whose obsessive TikTok scrolling meant that everyone around him was repeatedly assaulted by short snatches of speech and music. The week before that on the train from Gatwick airport, I was regaled with a conversation between a young woman and her mother about the former’s presumably soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend.1

Notably, although teenagers are frequently accused of being the primary culprits, my observations suggest that the phenomenon is not restricted to any particular age group, gender, class or ethnicity. As several of the commenters on a Mumsnet discussion on this topic have pointed out, the culprits are just as likely to be harried parents handing over smart phones and tablets to their infants as they are to be inconsiderate teenagers.2

I’ve also seen plenty of older people engage in the practice. For instance, I once sat through a bus ride while an elderly English woman had her phone on speaker the entire time she was on hold with St George’s Hospital. Thus, everyone around her was subjected to the dubious delights of tinny elevator muzak interrupted by periodic updates about where she was in the phone queue. By the time I reached uni, after about thirty minutes of this, she was still fourth in line.

Like myself, I’m quite certain that various other people on the bus wanted nothing more than to forcibly remove her phone and chuck it out the window, but not a single person said anything. Instead, we contented ourselves with glares and eye rolls in the hope that she might get the message. In fact, never have I witnessed a London commuter ask someone to turn down the sound on their phone or to use headphones. Nor, for the record, have I done so myself.

Based on the responses to a recent article in the Guardian titled ‘Do you mind listening to that with headphones?’ How one little phrase revolutionised my commute, in which most commenters marvelled at the author’s bravery in saying something, annoyed silence seems to be the response of choice. But all evidence to the contrary,3 this is not a distinctively English reaction, given the endless articles and online discussions about the phenomenon, which typically consist of a chorus of complaints and a kind of impotence about how to respond—beyond occasional bravado about making a show of going up next to the person and playing one’s own device even louder.

So far, I’ve uncovered few serious attempts to analyse what one commentator has labelled ‘blasterbating’, although the general consensus seems to be that: 1) it’s become more common since Covid, and 2) the people who do it are selfish arseholes. In an article titled 17 intrepid attempts to make sense of those cretins who refuse to wear headphones on public transport, ‘Spackysteve’ seems to sum up the prevailing view in his observation that, ‘It is because they are cunts. There were cunts before smart phones too, but modern technology has allowed them to excel at being cunts’.

But while Spackysteve may well be right, the phenomenon does raise several larger questions. For instance, does the growing prevalence of the behaviour mean that we are collectively becoming bigger arseholes? And, if so, is this the proverbial canary in the coal mine for the imminent collapse of civilisation? Will we look back on this moment and say things like ‘Well, in hindsight we should have figured out the end was nigh when everyone started using their mobiles without headphones’.

For some observers, tongue-not-precisely-in-cheek, the answer to this question is clearly ‘yes’. To quote one commentator in the London Evening Standard:

There are many portents of our inexorable decline into barbarity: the collapse of trust in our institutions; increasing intolerance and extremism; the fact that a grab-bag of crisps is the size of a normal bag of crisps 10 years ago. The assumption that you are entitled to inflict the racket from your phone on your fellow commuters is the surest sign yet that we will soon be living in a post-apocalyptic cursed earth.

Still, imminent civilisational collapse or not, there are two things that interest me, anthropologically speaking, about the phenomenon. First, why has it become more common? And, second, why do we find it so intensely annoying? I suspect the answer to the former is less straightforward than ‘people are arseholes’, and the answer to the latter is less self-evident than ‘because it IS annoying—duh!’

The primary explanation I have seen for the question of why the practice has increased in recent times is Covid itself. The premise seems to be that we got so used to being in digitally-mediated bubbles during Covid lockdowns, we tend to act like we’re still in them when in public today. Concomitantly, because we didn’t interact in-person for close to two years, we basically forgot the rules of civility—or, alternatively, stopped caring about them entirely. For instance, a New York Times article on the erosion of mobile phone etiquette quotes a psychologist describing the phenomenon as ‘Covid-era norm erosion’.

Personally, I think the role of Covid is probably over-emphasised, partly because it downplays the ways that mobile phones themselves have steadily been transformed over the past decade into something rather different from a mere phone. Smart phones are basically a television, audiobook, computer, playstation and phone rolled into one, and each of these objects has a different set of norms around how we listen to it—norms that are generally built into the device itself.

For example, most televisions don’t come equipped with headphone jacks, based on the premise that they are supposed to be listened to out loud. This means that if one person wants to watch TV and the other doesn’t, generally the person who doesn’t want to watch must leave the room.4 Conversely, old-school phone calls were, by default, set up to be private rather than publicly broadcast. Likewise, the boombox was designed to be listened to out loud and the portable cassette player to be used with headphones—indeed, iPod minis (remember those?) didn’t work without them.

Contemporary smart phones are rather more ambiguous on this front. In fact, I’m not personally convinced that ‘phone’ is the best name for what is basically a flat screen ergonomically designed for eyes rather than ears.5 Notably, many smart phones no longer have a standard headphone jack—an observation that occasionally crops up in articles and Reddit discussions on the erosion of phone etiquette on transit.

This trend began with Apple’s decision in 2016 to remove the jack from the iPhone 7. While they framed this as a ‘courageous’ decision to abandon an ‘outdated’ analogue technology, customers were not happy, because a cheap, ubiquitous, interoperable device like standard headphones was no longer useable without a special dongle. Satiric products quickly followed, such as the Apple Plug, along with a spate of amusing commentary and fake footage.6 In one example of the latter, a Spanish ex-Apple engineer recounts Apple’s success in fooling customers into purchasing a new iPhone by removing the headphone jack, thereby forcing customers to either purchase dongles or expensive wireless headphones, and then adding insult to injury by calling it an ‘upgrade’.

Other manufacturers like Samsung have since followed suit and a growing number of smart phone brands don’t carry standard headphone jacks. Moreover, newer iPhones no longer come with headphones that connect to their charging port, thus basically forcing customers either purchase additional paraphernalia to use their headphones or, alternatively, to go wireless.

Indeed, it is unquestionably in the interest of companies like Apple and Samsung for people to purchase wireless earbuds, which have the advantage of being costly to purchase, easy to lose, and requiring replacement every few years regardless, because their batteries erode. The net result is that the standards and structures of contemporary smart phones have probably contributed somewhat to the reduction in headphone use—and the resultant social friction around it—in much the same way that the structures and standards of planes are more likely to bring passengers into conflict.

Still, I’m reasonably confident that not everyone blaring their phone on the tube is doing so because the poor dear has lost their earbuds and can’t afford to replace them, so other factors are clearly at work. Beyond sheer thoughtlessness, these seem to pertain primarily to different views about what constitutes acceptable public noise.

For instance, some people obviously think that if their volume is set on low, then the noise is no more troublesome than the variety of ambient sounds we are exposed to on transit—like the hum of conversations between passengers, the regular announcements over the loudspeakers, and the screeching of the trains themselves (which can admittedly reach ear-piercing levels on the Northern line). In other cases, it’s clear that people think others either will not mind, or will actively appreciate, what they are playing—like the older woman I recently witnessed on the tube listening to a classical concert without headphones, or the guy broadcasting the World Cup semi-final when England was playing Croatia.

Certainly, various commentators have suggested that some sounds from mobile devices are more offensive than others. The author of the aforementioned Guardian article specifically highlights noise from social media feeds, emphasising ‘That tinny quality to the noise, the abrupt stop and start of video and audio, the chaotic nature of each content type happening at once in the same tube carriage’.

However, I’m not convinced that the nature of the noise matters all that much. At heart, I think what most of us find irksome is the sense that someone else is inflicting their tastes, interests and activities (even those we might happen to share) on us unnecessarily. The thing about ambient noise is that we can’t control it, which is why we find it intrinsically less annoying than noise that can be controlled, but isn’t.7

It’s this sense that people could control the noise emitted from their phones but are choosing not to that is ultimately at the heart of the annoyance (or, perhaps more accurately, resentment) that a lack of headphones causes on transit. It’s not really about what they’re playing or watching and whether we like it or not, but the sense that they are inflicting their choices upon us regardless.

As a woman in the aforementioned New York Times article notes, ‘We can’t solve the jackhammer or noisy neighbors, usually. But you can put on a pair of headphones. There are so many social contracts that we all agree to, and this should be one of them’. And in the event that you’ve lost your wireless earbuds or—horrors!—forgotten to bring them without you, there’s even an alternative: the revolutionary idea of sitting quietly for the duration of your commute without looking at your phone.8

Related posts

Based on the litany of ills she recounted—like her boyfriend getting drunk and using her credit card to purchase £100 taxi-rides—he did indeed sound like a ‘fucking selfish twat’. Still, given that she was loudly conversing in speaker mode in a ‘quiet’ train carriage, this seemed like a pot-meet-kettle situation.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Super JoJo is a sadistic creation featuring what can only be described as the spawn of Satan. I have barely been able to refrain myself from smashing the devices on which I’ve heard it played (always at an earsplitting pitch). As one of the respondents to an article ranting about the lack of headphone use at airports noted of the noise coming from kids’ videos, ‘I’d rather hear screaming’. Me too, brother. Me too.

For example, I recently entered a train on the Central line during rush hour, only to find a guy sleeping in the carriage. While that in itself is not of particular note, the fact that he was taking up all four seats in the row most decidedly was. I spent an entertaining ten minutes watching everyone’s eyes light up when they stepped on the carriage, thinking that they were about to get a seat, only to find a clearly drunk guy taking up the entire row. Everyone glared and rolled their eyes, but no one said anything to him—and I’m reasonably confident that situation would not have changed if I had stayed on the train til the end of the line. I don’t think passengers would have tolerated this for long in any other country I’ve lived in (yes, including Canada*).

*The most aggressive encounters I’ve had with strangers on transit, including an episode where a random woman started making throat-slitting gestures and declaring, ‘I’m gonna cut you, bitch’, happened when I lived in Vancouver. In the discussion of body odour in my book Silent But Deadly, I recount an incident on the same bus route with an old lady who loudly declared to all and sundry that I stank.

Although in my case, this generally also involves a fair amount of yelling from upstairs about how I can still hear the TV and to turn the volume down further.

As anyone who has tried to have an old-school conversation with their smart phone pressed to their ear for more than two minutes will have intuited for themselves.* They might be a smart computer, but they are probably the dumbest actual phone in history.

*Although how holding your phone in front of your mouth is an improvement is anyone’s guess. As Zoe Williams has asked, ‘Millennials: oh my God, millennials, that thing you do where you hold the phone in front of your mouth and shout into it while you’re walking down the road, so that even the birds in the trees know what protein shake you had after your challenging workout, why do you do that?’

The gift that keeps on giving to meme-makers the world over, this footage of the Spanish comedian Juan Joya Borja, a.k.a. ‘El Risitas’, is a good illustration of the power of laughter alone to make people laugh. For the record, he’s actually recounting an incident where he was working at a restaurant and lost a bunch of mouldy frying pans while trying to clean them in the ocean—you can see the original translation here, although I’m not sure I recommend it, as it kind of ruins the magic to know what he’s actually saying.

For instance, when I lived in a condo in downtown Vancouver, I would go to sleep each night to the sounds of blaring traffic, dumpsters being rifled through for cans and bottles, drunken revellers, and dogs barking, but the one noise that drove me completely bonkers was when my music production neighbour would decide to start mixing tunes at 11pm.

The youngsters have even given it a name: ‘raw-dogging’. As an aside, I can think of little better illustration of the intergenerational differences between Generation X and Z than our respective associations for ‘raw-dogging’. For Gen-Xers, it conjures images of doing it doggy-style without a condom;* for Zoomers, it’s sitting on a seven-hour flight without doing anything.

*Or maybe that’s just me.