At the best of times, I am not a fan of going to the hairdresser. While I hate the forced chitchat, what I really hate is that they often don’t listen to what you want. I can date my dislike of hairdressers to my early twenties and a hairdressing salon in Townsville, Australia. You see, I’d saved up to get my hair cut at the most exclusive salon in town: Josephine’s. The haircut cost something like $50 – a veritable fortune in the 1990s.

Josephine herself cut my hair and I distinctly remember giving her detailed instructions on what I wanted. ‘Not a bob’, I told her; ‘I don’t want a bob’. Anyway, she cut my hair in between dealing with other clients – I believe she was colouring someone’s hair while cutting mine, as she was quite distracted. Of course, the haircut I ended up with was exactly what I didn’t want: a bob.

But the worst part of the experience wasn’t just that she’d completely ignored my instructions and that I’d forked out $50 I could ill afford for the privilege, but that I felt forced to lie when she finished blowdrying my hair and told me how great it looked. ‘Yes’, I responded unenthusiastically to her patently false assurances, as I pondered a haircut that made me look like I was pushing 50;1 ‘It’s great’. On the drive back to uni, I remember feeling a kind of angry impotence. ‘Why did I lie?’, I kept asking myself. ‘Why didn’t I say something?’

Unfortunately, my poor brother-in-law was the first person to see me when I got to uni. He greeted me and I promptly burst into tears. These were tears of frustrated anger but, still, tears are tears, and particularly embarrassing in front of your new brother-in-law, who was completely bemused by my reaction (and I think has been slightly concerned ever since that I will randomly start bawling when he greets me).

The worst part is that I’m not remotely vain about my hair. Bad haircuts don’t faze me – I’ve had plenty over the years. Hell, I’ve given myself plenty, as I cut my own hair for the latter half of my twenties and into my early thirties. Sometimes it looked okay,2 but other times, especially when I wasn’t careful enough about lifting before I cut, it was distinctly uneven – shorn in some places, cut in others. In fact, one haircut I gave myself after we moved to Vancouver was so bad that I had to cover the bald spots with brown eyeshadow until my hair grew back. At that point, my sister staged an intervention3 and paid for me to see her hairdresser, who I had for the next decade.

But since we’ve moved to London, I’ve not had much luck finding a decent hairdresser, in part because the turnover at local salons seems to be so high but also because I have a limit to how far I will travel (half a mile) and how much I am willing to pay (£45). My response has been to grow my hair, and only get it cut two or three times a year.

However, last weekend, I decided to go back to having short hair, so I went to a salon nearby, armed with some pictures – not, mind you, of actresses or models that I expected to be magically transformed into, but that showed the kind of cut I wanted. The hairdresser took one brief glimpse at the photos, seeming taken aback that I had four. ‘Yes, I know exactly what you have in mind’ she said authoritatively, before proceeding to ignore the pictures completely.

The cut I ended up with is not terrible – I’ve had far worse – but it’s not great either, and, most importantly, is markedly shorter than I asked for. Tellingly, while she requested permission to take ‘before’ pictures for her portfolio, she didn’t ask to take any photos afterwards. The best she could say was that ‘It takes years off your age’.4 ‘Yes’, I responded unenthusiastically; ‘It’s great’. Thus, I once again found myself in the exact same position as my 23-year-old self. I left the salon feeling annoyed with myself for not pointing out that the cut she’d given me bore no resemblance to the cut I’d asked for, and wondering why I still can’t say this to a hairdresser a quarter of a century later.

I’m clearly not alone in this reluctance. For example, an American survey commissioned by Toni & Guy hair salons found that while one in five of the women surveyed had left the salon in tears after a cut, only one in ten customers had refused to pay the bill.5 That figure seems relatively high to me, and I suspect a recent UK survey is more accurate. It found that only 5% of women have refused to pay for a bad cut, despite the fact that 45% have been disappointed with the outcome of a hair appointment and 33% said that their stylist didn’t listen to what they wanted. For the most part, women tend to express our displeasure by going elsewhere, or leaving an anonymous negative review.

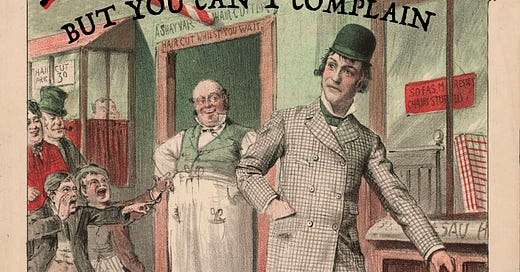

Notably, this is not exclusively a women’s problem. For example, a GQ article titled ‘How to tell your barber you don’t like your haircut’ suggests that it’s just as difficult for men to complain about their hair being butchered at the barber shop. To quote the article’s discussion of a scenario that should sound strikingly familiar,

‘And yet so many of us lie to our hairdresser. “Oh, yes, that looks fine,” we trill, as we pay, before racing to the nearest hat shop, cancelling all our plans… Rather than face it, they [men] suffer in silence or switch to another salon and risk ending up with another haircut they loathe, now with even less confidence to bring it up – and so the cycle continues until they end up lasering it off with clippers or adopting Jesus as a trichological icon’.

Now, some of the disappointment people experience after a trip to the hairdresser can no doubt be chalked up to the gap between expectation and reality, and the fact that hairdressers cannot perform miracles on their clients’ hair – transforming our thin locks into Helena Bonham Carter-style6 tresses. Alternatively, we all know of people who decide on a whim to change their style and are not prepared for the result.

Notably, when I got my hair cut last weekend, the hairdresser immediately asked me if I’d ever had short hair before, as she’d presumably learned to be leery of women requesting a dramatic change and then hating the outcome. In fact, when my sister started losing her hair during chemotherapy, the barber she asked to buzz it off initially refused to do so. It was only when she explained that she was undergoing cancer treatment and all her hair was falling out anyway that he was willing to proceed.

But the fact is that most of us don’t feel comfortable telling a hairdresser or barber that we’re not happy with our haircut, even when they have done an objectively bad job or have given us a very different cut from the one requested. In this respect, haircuts seem fundamentally different from other types of services, where people are more prepared to complain.

The difference becomes clear as soon as you compare haircuts to restaurant meals. For example, if you order a meal at a restaurant and are brought the wrong one, most people will speak up. Fewer people will complain about the quality of the meal, but I suspect that their number is greater than the volume of people willing to complain about a bad haircut, even though the latter has longer-term and vastly more public consequences than a dodgy meal.7

So what’s going on? Having given the matter some intensive thought over the past week (basically, every time I catch a glimpse of myself in a mirror), I think there’s several elements at play. The fact that hairdressing involves a degree of artistic skill as well as technical know-how is probably part of it. Typically, we don’t like criticising artworks in front of the artist who created them, although we’re perfectly happy to bag them out in private and, at least if we are art critics, in the pages of newspapers.8 This is perhaps why complaints about meals at restaurants are more common than complaints about haircuts: they are typically made to the server rather than the chef.

Yet, the same mix of artistry and technical skill is arguably true of tailors, but I assume that most people speak up if they’re not happy with the fit of the clothes being made. They certainly don’t expect the tailor’s feelings to be hurt when they request further alterations to improve the fit – that being precisely the point of getting a bespoke outfit in the first place. So why is hair different, given that, like a tailor-made suit, it is ostensibly tailored to you.

The public nature of the barber shop and hair salon is probably a factor here. Haircuts, unlike the act of getting clothes tailored, are generally a public experience. A conversation with your hairdresser is never just a private chat, because anyone sitting in the vicinity can hear it. Likewise, any complaints are going to be equally public. Add in the subjective dimension to assessments of a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ haircut and the fear of appearing vain, and you have an environment that seems virtually engineered to quell complaints.

However, to my mind, the key factor in our reluctance to call out bad haircuts is unquestionably the nature of hair itself. Hair, as anthropologists have long intuited, is a peculiar substance, being simultaneously of the body, but also separable from it. But it’s radically different from other bodily substances I have previously discussed on this Substack (farts, snot, spit and so forth) – so much so, that we don’t typically even think of it as a bodily excretion.9 Thus, while we don’t much like it when we find someone else’s hair in our soup, we are perfectly happy to wear a wig made of someone else’s hair – and, in fact, will pay a fortune for the privilege.

As the anthropologist Christopher Hallpike has observed, hair has a number of special characteristics that make it symbolically and ritually meaningful. Like nails, it grows constantly, and, like nails, it can be cut painlessly. It also grows in such great quantity that ‘individual hairs are almost numberless’. This, he suggests, is why hair is cross-culturally seen to be endowed with more vitality than other bodily substances such as ‘body dirt’ (presumably, faeces, urine, etc.) and nasal mucous, which is why it’s far more frequently used for the purposes of committing magical harm.10

Because of these unusual attributes, hair is never just hair, which is why people get upset about hairdressers mishandling their locks. But because it constantly replenishes itself, a bad haircut is simultaneously irreparable – especially if your stylist has lopped too much off – and temporary, given that it will grow back. As the old joke goes, the difference between a good and bad haircut is approximately three weeks.

The result is that most of us – rightly or wrongly – suffer in silence through a bad cut: angry and resentful, but not sure we have the right to feel that way and vaguely embarrassed that it matters so much to us. After all, we tell ourselves, it’s just hair. I guess I also figure that life is short. I mean, so is my hair, but at least I can console myself in the knowledge that in two months time, I’ll have the haircut I wanted a week ago.

Related posts

Reader, I had seen my future. The haircut she gave me is basically the haircut I’ve had for the past four years.

Or so I thought. After I stopped cutting my hair, a friend told me how relieved she was that I was now getting it done professionally because it had looked terrible and she hadn’t known how to tell me.

Note to any fellow academics reading this. See my usage of the word ‘intervention’ here? This is the correct way to use the term: you interfere with something to change the outcome. Giving feedback on someone else’s talk isn’t an ‘intervention’, it’s feedback, or, at best, a discussion. I hate to break it to you, but even if a bunch of you do it – in, the context of, say, a conference panel – it’s still just a discussion. If I end up writing a piece called ‘I don’t think that word means what you think it means’, ‘intervention’ will definitely be in it.

It doesn’t, unless she thought I was 55.

Interestingly, only one in five respondents had refused to leave a tip, which just goes to show that tipping, despite what people tell themselves, is not voluntary. You can read my thoughts on tipping – including at hairdressers – here.

My hair icon in the eighties, so I was mightily disappointed to later learn that her hair in A Room with a View was largely due to a head full of extensions procured from a (priorly) long-haired extra in the film.

Unless, of course, that meal gives you a violent case of public vomiting or diarrhoea. I have had some experience of the former, after eating a dodgy prawn salad several hours before I was due to give a talk. I got about five minutes into the talk and the room suddenly started spinning so badly I could barely stand. With the help of colleagues, I made it to the closest public toilet, where I proceeded to vomit repeatedly – and relatively publicly – for what felt like the next hour.

Like Jonathan Jones in his infamous review of Damien Hurst’s ‘Two Weeks One Summer’ exhibition, which contains gems like ‘The last time I saw paintings as deluded as Damien Hirst’s latest works, the artist’s name was Saif al-Islam Gaddafi’ and ‘This is the kind of kitsch that is foisted on helpless peoples by Neros and Hitlers and such tyrants so beyond normal restraint or criticism they believe they are artists’.

Head hair, at least. Pubic hair is an entirely different matter. As far as I know, no one is donning fake pubic hair. Actually, scrap that. I just did a Google search and, lo and behold, you can purchase fake pubic hair from Amazon that appears to be made from actual human hair – albeit from the head rather than the nether regions. There’s only one review so far: ‘Bought these a few days ago and there [sic] just like real ones! So good think everyone should buy’. I have questions, so be prepared for a future Substack post on this topic.

Although that might also be because it’s considerably less revolting to harvest.