What's in a name?

In 2008, Deborah Campbell called a local ShopRite in New Jersey to request a birthday cake for her three-year-old son. However, when they heard her son’s name, the bakery department baulked at the request. Little Adolf Hitler Campbell, they said, would need to get his cake decorated elsewhere. Deborah eventually found a Walmart in Pennsylvania willing to create a personalised cake for Adolf, but the case was now national news – especially when the press found out that his younger sisters were named JoyceLynn Aryan Nation Campbell and Honszlynn Hinler1 Jeannie Campbell.

For his part, Adolf’s father, Heath Campbell, didn’t see what all the fuss was about. He told reporters that he’d named his son after Adolf Hitler because he liked the name and because no one else in the world would have it. ‘I think people need to take their heads out of the cloud they’ve been in and start focusing on the future and not the past’, he stated. ‘They need to accept a name. A name’s a name. The kid isn’t going to grow up and do what he [Hitler] did’.

Moving across the pond, now consider little Jensen Jay Alexander Bikey Carlisle Duff Elliot Fox Iwelumo Marney Mears Paterson Thompson Wallace Preston, born in 2011 in Lancashire. For those who aren’t lifelong fans of the Burnley football club, he is named after the 14 members of the team who beat Nottingham Forest in a football match in August 2011. When interviewed by the Daily Mail, Stephen Preston, the boy’s father, explained, ‘We have seven children between us and this is going to be our last so we thought why not go for something different’.

While the Prestons’ decision to give their child 14 personal names might seem fairly innocuous – at least in comparison to naming your kid Adolf Hitler – what both these cases have in common is parents’ willingness to inflict their personal interests and ideologies on their children’s names,2 in ways that are likely to ramify for the rest of their kids’ lives. Although Adolf Hitler arguably drew the short straw, I imagine that Jensen will be similarly cursing his parents every time he’s required to put his legal name on a form, given that most have limits of well under 106 characters.

Based on the number of women who have named their child ‘Renesmee’ after reading Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, one should never underestimate the willingness of parents to saddle their children with godawful names. Indeed, my sister-in-law, a primary school teacher for more than 30 years in a regional Australian town, has numerous stories to tell of students with names like ‘Thor’ and ‘Pocahontas’ (siblings), ‘Fish’ and ‘Chips’ (another set of siblings), and Shithéad and Lemón (siblings again). Celebrities are also notorious offenders in the daft-kids’-names department – as Diva Thin Muffin (Frank Zappa’s daughter) and FiFi Trixibelle (Bob Geldof and Paula Yates’ daughter) can attest.

In light of the potential ramifications of an ill-chosen (or, in some cases, frankly malicious) denomination, some countries have laws restricting the personal names parents can give their children, including Germany, Denmark, Sweden,3 Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, New Zealand, Malaysia, and France. Until 1993, France had some of the strictest laws in the world, compelling new parents to choose from a list of acceptable baby names. However, while this requirement has been dropped, courts can still ban personal names if they decide the chosen appellation is against the child’s best interests.

According to the French newspaper The Local, names that have been rejected by French courts include ‘Clitorine’, ‘Vagina’,4 ‘Nutella’, ‘Fraise’ (French for ‘Strawberry’), ‘Jihad’, and names of known terrorists like Mohamed Merah. Oddly, given the general French antipathy towards Anglo Saxons, ‘Mini-Cooper’ and ‘Prince-William’ have also been nixed by the courts.

Although we tend to think of terrible children’s names as a recent trend driven by celebrities, bad names – or at least stories about such – have been around for a long time. Witness the scene in Silkwood where Fred Ward’s character recounts an old joke about how a child in a Native American tribe got his name.5 The joke implies that poorly chosen names are a universal phenomenon: one that cuts across time and space. However, the possibility of being landed with a dud name is largely contingent on the rules around naming in place in any given culture – a topic that anthropologists have studied in some detail.

Anthropologists specialising in onomastics, or name studies, suggest that the practice of bestowing personal names is universal. To quote the anthropologist Ellen Bramwell, ‘Labelling people and their surrounding landscape seems to be something which is ingrained into human cultural practice’. However, differences abound in the kind of name bestowed and the rituals surrounding the process. Moreover, people might receive different names at different stages of their life, and their name might be used freely, kept secret or treated as something sanctified that must be used with care.

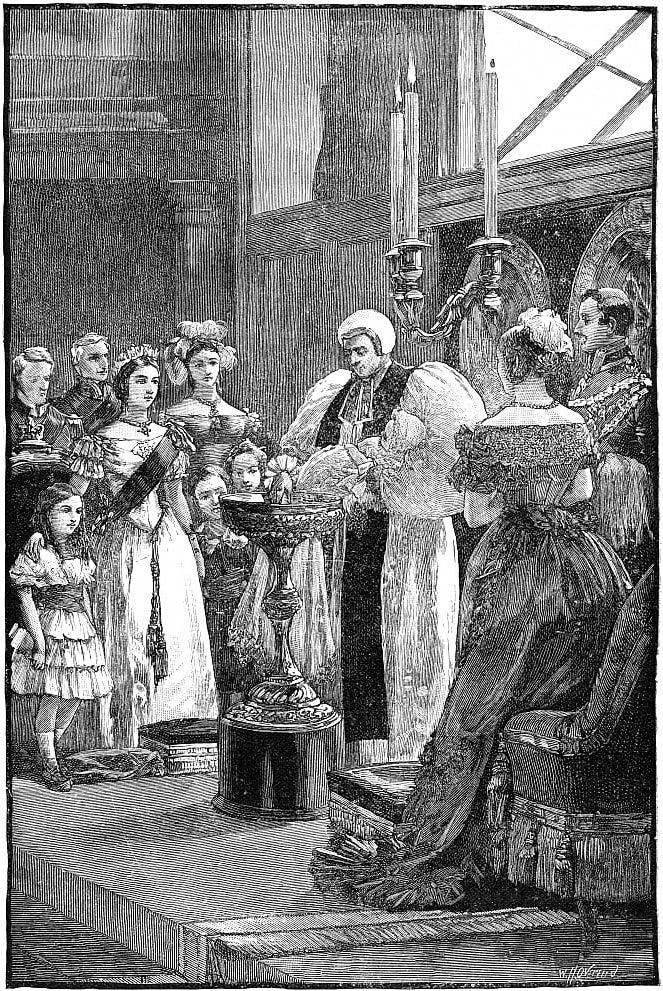

For example, in Christian cultures, children formally received their names when ritually christened in a church – this is, of course, why we still call personal names ‘Christian’ names, even though many of us have never been christened. In Judaism, on the other hand, children receive a Hebrew name in addition to their secular name, with the former name restricted to important rites of passage and other religious ceremonies (bar/bat mitzvah, wedding, etc.).

Conversely, in areas with high infant mortality rates, the child’s name is commonly delayed until their survival looks assured. According to the anthropologist Nancy Scheper Hughes, this was common practice in the favela where she conducted fieldwork in Northeast Brazil in the 1980s. One way mothers protected themselves from strong, emotional attachments to their infants was by leaving them unnamed until they began to walk or talk.

While cultural differences abound in when personal names are bestowed and how frequently they are used, they universally perform the function of simultaneously classifying and individualising their bearer. However, the extent to which they do one or the other depends on the culture in question. For example, the individualising role of names is strongly emphasised in contemporary Anglo-American contexts, which is how the actor Jason Lee’s kid ended up being named ‘Pilot Inspektor’ and Jermaine Jackson’s son ‘Jermajesty’. However, that depends on who is being classified: the kid or their parent.

According to the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, all proper names serve a classificatory function. Either the name identifies the named as part of a preordained class or identifies the person who gives the name. In his view, no matter how creative or free a name seems to be, it’s always an act of classification that reveals something either about the bearer or the bestower.6 Of course, most names simultaneously do both, a point he illustrates in relation to pedigree dogs.

Lévi-Strauss notes that the names of pedigree dogs have strict rules surrounding them in order to preserve their value and prestige. While they are formally registered under these names, the owners can, of course, decide to call the dog by whatever name they choose. The name they decide upon therefore reveals something about them – it might define them as commonplace, or eccentric and provocative, or an aesthete. Likewise, while celebrities’ children’s surnames serve as a way of establishing their pedigree, their personal names serve as a means not of classifying them but their parents, reinforcing the latter’s own classification (or ‘brand’, to use contemporary parlance) as ‘eccentric’, ‘provocative’, ‘whimsical’, ‘bohemian’, ‘whacky’, etc.

In effect, what Lévi-Strauss’s work suggests is that naming practices are always about class – either the child as a member of a class, or the parent as ‘a member of the class formed by my own wishes and tastes’. These tastes, as the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu subsequently showed, are themselves fundamentally social, rather than individual.

Although Bourdieu didn’t specifically focus on naming practices, the effect of class on our tastes is as true of the names we choose for our children as the type of tea or coffee we consume.7 For example, in The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility, the economic historian Gregory Clark discusses the extremely high prevalence of girls named ‘Eleanor’ at Oxford University between 2008-2013 and the correspondingly low proportion of girls named ‘Shannon’.

This is a good illustration of the class connotations of these names and the ways in which they consciously or unconsciously inform parents’ choices – a phenomenon also illustrated when people decide to have their name changed by deed poll. One famous example is the birth name of the Australian actress Portia de Rossi: Amanda Lee Rogers. In interviews, de Rossi indicated that she never felt like an ‘Amanda’ and that she chose her new name because it sounded classier and more exotic than her birth name.

Of course, personal names aren’t just associated with class (and, obviously, sex) but with ethnicity as well. An unfortunate side effect of this is name-based discrimination. As Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner discuss in Freakonomics, Americans with ‘black’-sounding names like ‘Roshanda’ or ‘DeShawn’ are less likely to get called for a job interview than their ‘Jake’ and ‘Amy’ counterparts – a phenomenon that has also been reported for people with Arab American names.

But names also serve to locate their bearer in less obvious ways as well, including their age, given that personal names come in and out of fashion. Indeed, numerous commentators suggest that the current trend for ‘old-fashioned’ names is evidence of a 100-year rule, with names falling out of fashion from one generation to the next, only to reappear as ‘fresh’ alternatives a few generations down the line.

However, the preoccupation with old-fashioned names is also class-based. In Australia, you’re currently far more likely to find more ‘Alfreds’ and ‘Ediths’ amongst the middle class and a lot more idiosyncratic names like ‘Jaxxyn’ and ‘Xyza’ amongst the working class, further bolstering Lévi-Strauss’s point that names always classify, even if (or, more accurately, especially if), they are highly individualised.

In sum, as the psychoanalyst Mavis Himes notes in The Power of Names, ‘A given name is never random. It trickles down through the unconscious of the name-givers. While life and birth circumstances, moral qualities, physical characteristics, and simple preference (we just liked the sound of it) may contribute to the choice of a given name, it is rarely that neutral in its selection’. While we often imagine that names tell us who we are, the reality is that they actually tell everyone else who we are – and, more importantly, who our parents are, which is why you should always be careful what you name your kid, not just for their sake, but for yours!

Related posts

The name was widely taken as a reference to Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s chief architect of the ‘Final Solution’, although Adolf’s father did later go on to have a son named Heinrich Hons Campbell.

You can also spot the child of hippies a mile away. I once taught a student named ‘Meadow Trail’ who, I can only assume, was raised in a commune.

Rejected names in Sweden include ‘Ikea’, ‘Superman’ and ‘Brfxxccxxmnpcccclllmmnprxvclmnckssqlbb11116’.*

*Although this one might possibly be the result of a cat deciding to plonk itself down on the computer keyboard just as the parent went to push the ‘submit’ button on an online pre-registration for a birth certificate.

People have also been advised not to call their child ‘Anal’, although this name has not yet been tested in the French courts.

This was one of my dad’s favourite jokes when I was growing up.

In Lee and Jackson’s case this is presumably that the bestower is a bit of a nob.

In Watching the English, the anthropologist Kate Fox highlights the class patterns in tea drinking in the UK, with the strength of the tea inversely correlated with social class: the working class prefer strong black tea like PG Tips (colloquially known as ‘builders’ tea’), while the upper class tend to fancy weaker brews like Earl Grey.