Once again, a debt of gratitude is owed to the anthropologist Marcelo Pisarro, who independently converged on the significance of this topic. It was Marcelo who directed me to the Tenement Museum’s blog, and his observations about gender, spitting and football have been incorporated into this piece.

While I was out walking recently, I spotted a man sitting on a park bench with his dog on his lap. The dog was enthusiastically licking the man’s face, including his lips, and the man was laughing in response. Not being a dog person, I was slightly revolted by the sight, although admittedly not as revolted as seeing Kristen Wiig’s intensely committed Saturday Night Live performance as a woman with a year’s worth of pent-up PMS tonguing her dog.

The science studies scholar Donna Haraway has written about this topic at some length in her book When Species Meet. In her vivid1 illustration of the intertwined relationships between canines and humans, she writes of her dog, Cayenne Pepper,

‘Her red merle Australian shepherd’s quick and lithe tongue has swabbed the tissues of my tonsils, with all their eager immune system receptors. Who knows where my chemical receptors carried her messages or what she took from my cellular system for distinguishing self from other and binding outside to inside… We are, constitutively, companion species. We make each other up, in the flesh’.

Contrast this affectionate account of sharing spit with one’s dog to media reports last year about a wave of ‘sushi terrorism’ gripping Japan. Essentially, a series of social media posts revealed that pranksters at conveyor belt sushi restaurants (kaitenzushi) had been ‘interfering’ with the food. Contrary to the image from American Pie that this term immediately conjures,2 this basically consisted of customers licking things on the sly: communal soy sauce bottles, rims of tea cups, their fingers, which they then touched pieces of sushi with, and so on. The footage sparked immediate outrage in Japan and saw sushi chain stocks plummet in response.

Although we don’t, as far as I know, have any cases of sushi terrorism in western contexts, I assume that the reaction would be much the same – at least, based on widespread fears about vengeful servers spitting in food at restaurants, depicted to outlandish effect in the Ryan Reynolds movie Waiting. However, given that dogs are perfectly happy to eat both vomit and faeces, and are prone to licking their own arses, the contrasting responses to the spit of strangers vs that of a beloved pet are clearly quite revealing, suggesting something significant about our relationship with saliva.

To date, this is not a topic that has come up on this Substack, except in passing, which strikes me as a significant oversight for someone intensely fascinated by bodily emissions. In point of fact, saliva is an especially interesting excretion to contemplate, because it’s one of the few substances we interact with inside another person’s body – via the act of tongue kissing (a.k.a. ‘pashing’, as we call it in Australia).

Of course, it’s precisely because of the saliva exchange that occurs during such kissing that it’s far from the universal gesture of romance and intimacy that we assume – as I noted in my post on hugging. But our lack of concern about kissing, despite the bacterial transfer it entails,3 is a good illustration of the contextual nature of the disgust saliva produces.

As the historian William Miller notes in his book The Anatomy of Disgust, we generally find saliva in the mouth unproblematic, because it’s ‘safely where it belongs’. But as soon as it leaves its natural home, it becomes the object of disgust – as a thought experiment posed by the psychologist Gordon Allport in the 1950s illustrates. To quote Allport, ‘Think first of swallowing the saliva in your mouth, or do so. Then imagine expectorating it into a tumbler and drinking it! What seemed natural and “mine” suddenly becomes disgusting and alien’.

Likewise, while we happily pash our romantic partners, most of us would be markedly less willing to drink a shot glass full of their spit. Indeed, we don’t generally like to be reminded of the saliva transfer that happens during a passionate snog, which is why Hollywood kisses that end with a visible trail of saliva between the lips of the protagonists (such as this scene from the 1994 version of Little Women) regularly feature in lists of the ‘grossest’ movie kisses.

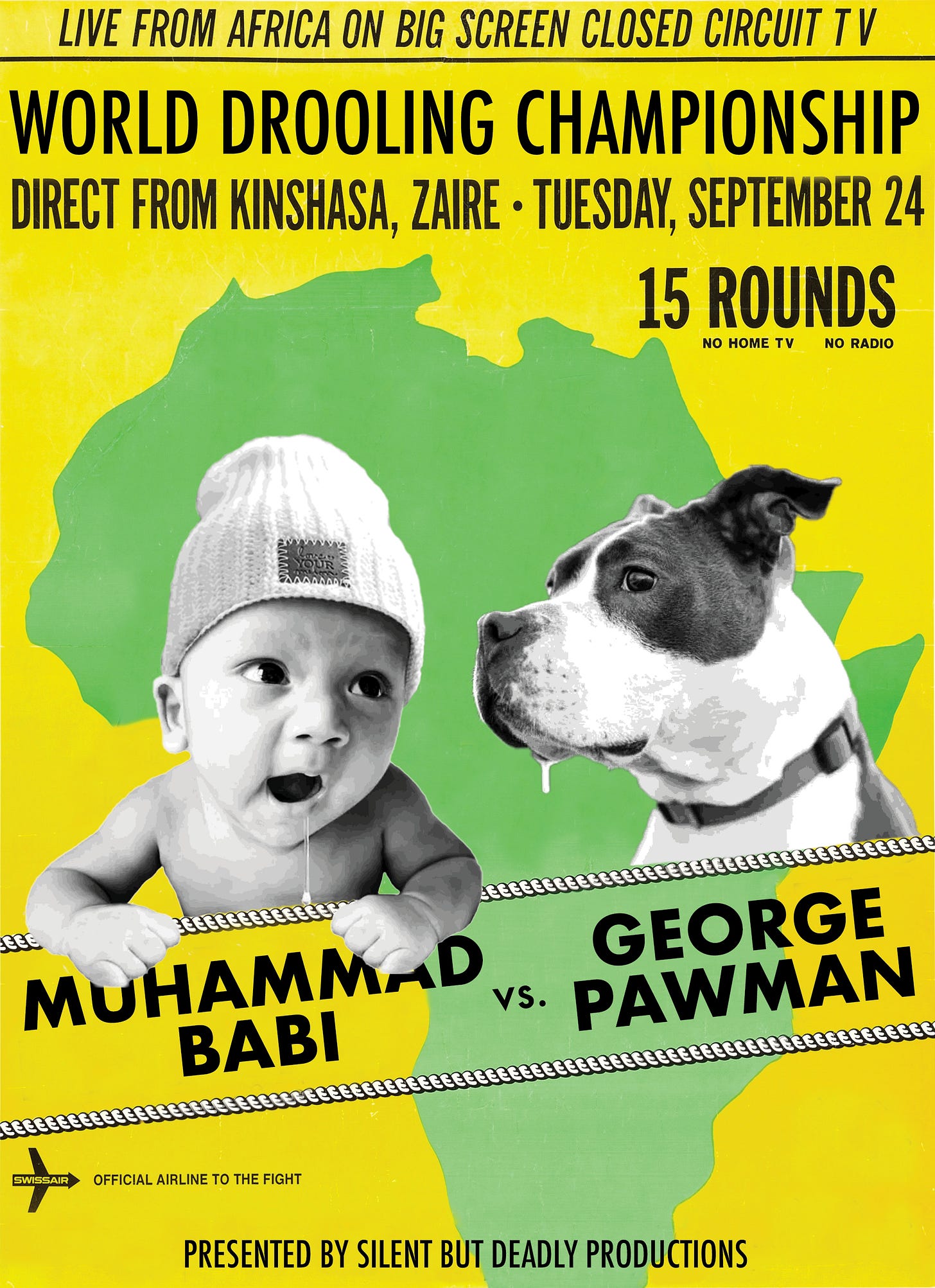

Complicating matters further is the fact that saliva outside the mouth takes, by my count, at least three distinct forms: drool – its most liquid form, common to babies, dogs and open-mouthed sleepers; the ‘loogie’4 – a mixture of saliva and phlegm, forcefully ejaculated or ‘expectorated’ from the back of the throat; and, finally, spittle – less solid than the loogie but more viscous than drool, and occasionally wiped from lips after kisses or seen bubbling out the mouths of babies.

Arguably, our responses to these three forms of saliva are different, something alluded to in the anthropologist Mary Douglas’s discussion of bodily substances, albeit not addressed directly. Douglas, of course, has been central to theorising the symbolic meanings of bodily emissions, suggesting that we perceive them as both powerful and polluting. But Douglas also points to the role that the natural attributes of these substances play.

Take tears vs saliva – a comparison Douglas discusses at length. As she notes, tears constitute a general exception to our dislike of bodily emissions. Why, she asks, is saliva more pollution-worthy than tears? Douglas suggests that this is partly due to the physical attributes of the substances themselves – snot and saliva are more treacle-like than water. Tears, in contrast, are naturally pre-empted by the symbolism of washing. In her words,

‘Tears are like rivers of moving water. They purify, cleanse, bathe the eyes, so how can they pollute? But more significantly tears are not related to the bodily functions of digestion or procreation. Therefore their scope for symbolising social relations and social processes is narrower’.

Applying this same logic to saliva’s three forms would lead us to hypothesise that the more viscous saliva becomes, the more polluting we perceive it to be. And, sure enough, that does seem to be the case. Most of us are familiar with the spit-clean: when parents (well, primarily mothers) spit into a hanky to clean their child’s face.5 Likewise, geologists also frequently use spit to clean drill core and inspect the minerals it contains.6

Loogies, on the other hand, are seen to be highly polluting – a view we held long before spitting became associated with disease in general, and tuberculosis in particular. According to the German sociologist Norbert Elias (discussed in detail in my related post on snot), it wasn’t until the seventeenth century that spitting in public started to be considered distasteful in Europe – not coincidentally, about the same time that a concern arose about how and where (and with what!) the nose was blown. For example, a French book of manners from 1672 advised, ‘Formerly, for example, it was permitted to spit on the ground before people of rank, and was sufficient to put one’s foot on the sputum. Today that is an indecency’.

Notice the distinction made between the act of spitting and the sputum itself. Even when the former was acceptable, the latter was supposed to be hidden from sight. An element of this logic is evident in the anti-spitting sign above, from a turn-of-the-century American public health campaign. The sign isn’t telling people not to spit at all; rather, it’s telling them to spit in the gutter rather than on the sidewalk.

According to the Tenement Museum, one nineteenth-century investigation in Baltimore found that a single city block could collect between 2,000-4,000 individual deposits of spit in a single week, so there is little question that spitting was a serious public nuisance. Women were especially affected by the habit, ‘as any trip outside the home meant collecting spit and phlegm along the hems of their floor length dresses’. This, in combination with the fact that they were generally the victims of loogies rather than the perpetrators of them,7 helps to explain why organisations like the Ladies Health Protective Association were at the forefront of anti-spitting campaigns.

However, such campaigns clearly point to the cultural dimension to conceptions of pollution, and their disconnect from actual biological contamination. After all, from the standpoint of TB prevention, spitting is spitting. The public health risk is aerosol transmission of the bacteria, not the likelihood of your shoe or dress coming into contact with a loogie (unpleasant though that may be). Likewise, if cultural and biological contamination mapped directly onto each other, dog owners would be avoiding their pets’ saliva like the literal plague and we wouldn’t be talking about pranksters licking sauce bottles at sushi restaurants as ‘terrorists’.

What these examples point to is the fact that our responses to saliva are tied up with our relationships to the creatures (both human and non-human) it comes from, and, in particular, whether they are intimates or strangers. As the anthropologist Janet Carsten has discussed in her book After Kinship, kinship is made not just through ties of blood and marriage, but through shared substances. Parents think nothing of wiping the spit off a baby’s chin, or sharing food or drinks with their children (and vice versa). Similarly, couples share food, drinks, kisses and, occasionally, toothbrushes,8 without a second thought.

This observation is borne out by experimental research by evolutionary psychologists suggesting that children learn from a young age to identify saliva sharing as a marker of the closeness of a social relationship. The researchers found that ‘Toddlers and infants expect that people who share saliva will respond to one another in distress’. In effect, sharing saliva is a marker of intimacy in much the same way as voluntarily farting around someone.9

So, in the end it turns out that while saliva is about disgust and contempt (at least, if you choose to expectorate it in a stranger’s face), it’s also about love – as toddlers have clearly intuited. And while ‘love is spit’ is probably not going to be embraced by Hallmark this coming Valentine’s Day, when you kiss your loved one that morning, all I can say is ‘bottoms up!’

Related posts

That’s code for ‘nauseating’. Clearly, Haraway needs to watch The Truth About Cats and Dogs and the ‘You can love your pets, but just don’t love your pets’ speech, although admittedly that bit of wisdom is precipitated by a guy letting his cat lick his face for three hours.

Well, at least for me.

According to one academic study, a ten-second kiss leads to an average total transfer of 80 million bacteria.

For ease of reference, I will use the American term to differentiate it from the more widely used ‘spit’, which has a broader meaning. In case you’re wondering, beyond its indisputably American origins, the etymology of ‘loogie’ is uncertain. According to Wiktionary, it has been variously theorised to have its roots in the name of the baseball player Lou Gehrig, or is a possible variant of ‘booger’. Those interested in boogers (anyone voluntarily choosing to read a post on spit, I assume) can read more about them in my post on nose-picking.

Okay, yes, according to this theory, drool should take precedence over spittle, but the latter is typically easier to conjure, drool requiring the mouth to hang open for periods that only babies, dogs and sleepers seem comfortable with. It’s only when you go to the dentist that you realise just how much drool you produce when your mouth hangs open, thus requiring the regular application of a spit-sucker. Personally, I think it would be interesting to learn more about what dentists think of saliva, given that they are hands-deep in the stuff all day. Sadly, as far as I know, no one has seen fit to study this.

Although drillers, knowing geologists like to do this, apparently have a habit of pissing on the core samples.

Then, as now, public spitting was strongly gendered, something particularly apparent when women break gendered spitting norms. A perfect contemporary illustration can be found in the Women’s World Cup match in 2019 between England and Cameroon. A match better known for the incessant drama and controversy on the pitch than the quality of the football it contained, the most striking moment of the game was not the actual slap that occurred, but a Cameroonian defender spitting (possibly accidentally, possibly not) on the arm of the English forward, whose resultant scream was so loud that it could be heard from the stands. Reviewing the incident at half-time, the BBC, in its wisdom, chose to blur out the Cameroonian defender’s face and neck. As the sports reporter Giles Smith later pointed out, this is a form of treatment that ‘television commonly reserves for celebrities’ car number plates and people with pending court cases’, so it was somewhat surprising to see it utilised in footage of a football match, given the ubiquity of spitting in the men’s game.

Or, rather, I occasionally use my husband’s toothbrush when we travel – in part because I often forget to take my own but also because he goes to the bother of packing a sonic toothbrush. In all honesty, I’m not sure he’s aware that I do this, but surely he wouldn’t mind – like Spanish-speakers always say, Mi cepillo de dientes, su cepillo de dientes.

What, did you think I’d write a whole post on bodily emissions without mentioning them?