She-bagging, beach cabanas and the unwritten rules around 'bagsing' public space

This is a follow-up to my recent post on seating etiquette on transit, although it goes in some pretty random directions.

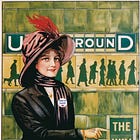

I have recently had cause to think more about seating etiquette. The catalyst was another incident on the tube, this one involving a trainload of children and harried teachers, who had presumably just finished a school excursion at one of the many museums in central London.

As the carriage was standing room only, I stood in front of a gaggle of young girls chatting animatedly. To my initial delight, after a couple of stops, the girl sitting directly in front of me got up. However, her friend immediately placed her backpack on the now-vacant seat. This was presumably to show that the seat was reserved and that the girl would be returning to it after chatting to some friends a few aisles down.

A teacher sitting nearby noticed me eyeing off the seat and said to the girl minding it for her friend, ‘You can’t claim empty seats on the train; someone’s going to take that seat!’ The girl, who was probably all of nine, then looked at me uncertainly. I reiterated her teacher’s point about not being able to claim seats on trains, noting virtuously that I wouldn’t take the seat, but that someone else would unquestionably claim it at the next stop.

At this point, the issue became moot because the original girl returned to the seat and wisely chose not to leave it again until they reached their destination.1 Still, I can understand the girls’ confusion, because there are plenty of contexts where it is acceptable to reserve seats for people by placing bags or coats on them, so the reasons why it is not appropriate to do this on the tube are not as obvious as they might seem.

This was brought into sharp relief a week or so after the incident, when I was at Stansted Airport waiting for a much-delayed flight to Denmark. When I got to the gate, there were very few available seats, most being covered in either bodies, bags or jackets. For instance, one woman had her bag on the seat next to her and her jacket on a third, and my immediate assumption was that she was minding the seats for someone. As there happened to be a seat nearby with nothing on it, I went to that one instead, asking the woman sitting next to it, ‘Is this seat taken?’, before sitting down.

Shortly afterwards, another women spotted the same two seats I’d originally noticed and asked the woman if they were taken. The woman shook her head and somewhat reluctantly removed her jacket so the newcomer could sit down. Notably, she didn’t bother to move her bag, despite the fact that the boarding gate was now standing room only.

Clearly, the woman at the airport was ‘she-bagging’:2 selfishly denying another passenger a seat by hogging it herself. While this a behaviour that drives many of us nuts (myself included), what this incident shows is that airports are a context where it’s considered acceptable to claim additional seats. That we generally ask ‘Is this seat taken?’ is an implicit acknowledgement of other people’s prior rights to seating that is currently vacant. The same is true of cafes and cinemas, where people regularly place bags and coats on seats to show that they have been claimed for someone—a practice that most of us would see as legitimate.

So why is it acceptable to reserve seats for others at airports but not on buses or the tube? After all, unlike cafes and cinemas, both are transitional spaces rather than destinations in their own right.

My suspicion is that the difference relates primarily to the mobile nature of transit in contrast to the stationary nature of airport gates,3 and the resultant possibility that a jacket or bag on a seat symbolises a person who has temporarily absented themselves to go to the loo or get a bite to eat. For obvious reasons, this is not possible on inner-city transit—school excursions on the tube apparently excepted. In other words, bags on seats at airports can represent either illegitimate she-bagging or legitimate proxies for absentee passengers, and we’re never sure which it is. This is why we typically ask ‘Is this seat taken?’ before sitting.4

Still, there are limits to how long an absent person can continue to legitimately claim space at an airport gate, especially if the gate is crowded. If you choose to do an extended bout of duty-free shopping with your kids while your partner guards your bank of seats, expect death glares on your return to the gate if it’s a full flight.

The same applies to cinemas and cafes, where there are social limits to people’s tolerance for individuals claiming seats for absent others. In fact, at the local cinema we used to frequent in Vancouver, an ad would run at the beginning of each film to remind cinema goers of common courtesies such as turning their mobile phone off before the movie started and not hogging too many seats for friends. This part of the ad featured a cartoon image of a row of cinema seats covered in jackets, bags and a teddy bear, and a voiceover saying, ‘It’s okay to claim a couple of seats for friends, but it’s not okay to take up an entire row’.

Interestingly, the question of the social limits of claims to public space is a topic that is currently playing out on Australian beaches in relation to the use of beach cabanas. These are the temporary shade structures set up by beach goers to protect themselves from the brutal Australian sun, and have long been a fixture on Aussie beaches. However, as beach cabanas have become more common, there is growing concern about the amount of space they take up.

For advocates, they are little different from beach towels. According to one proponent, ‘As soon as you put down a towel on the beach, you’re effectively carving out that section of the beach to lie upon’. However, opponents say that ‘entitled cabana crews are hogging public space and disrespecting other beachgoers’.

Particular ire has been directed towards the growing volume of beach goers who arrive at the crack of dawn to set up a cabana for use later that day—i.e., claiming a prime spot before they actually use it. Even Australia’s prime minister, Anthony Albanese, has weighed in on the debate, declaring that the use of beach cabanas to reserve prime spots for later usage is ‘not on’ and goes against Australian values of fairness and equality.

In the debates about beach cabanas, direct comparisons have been drawn between cabana-staking and she-bagging. To quote a recent commentary suggesting that the cabana wars are much ado about nothing, ‘You let one person bang pegs into the sand and then what? People will start going to the park at 9am to claim a barbecue. They’ll put their bag on the next seat so no one else can sit there. Talk about un-Australian’.

Although intended as satire, the same principles are actually at play in these examples, which all relate to claims to public space and how we evaluate their legitimacy. Anthropologically speaking, what’s so fascinating about public space is that it’s constantly negotiated. Unlike private space, our claims to it are always temporary and subject to a social license.

Having given the matter some thought, I think the best way of understanding rights to seating in public space is through the concept of ‘bagsing’. Although British in origin, I’ve never heard it employed outside Australia or New Zealand. For those unfamiliar with the term, ‘bagsing’ is not about actual bags (although as I go onto discuss, it can be). Basically, it’s synonymous with ‘calling dibs’ on something and is likewise associated with children. As Purchase Man notes in a tongue-in-cheek article on the topic, ‘Bagsing is the Geneva Convention of childhood’.

In what Purchase Man describes as a ‘bagsing economy’, ‘ownership is based not on inheritance, purchase, gift, right or forceful seizure, but is invoked upon the bagser being the first to utter “bags” followed by the bagsed item’. Basically, bagsing gives you ownership over what you’ve claimed, which might be a right, a privilege or an object, but it can only be brought to bear over things that are up for grabs—i.e., not things owned by others.

Kids learn early on what’s bags-able versus what’s not, because while you can state that you ‘bags everything’, no one will take you seriously. Basically, the rules around bags-ability have to be locally negotiated.

For example, as I have previously discussed, my siblings and I frequently fought over our beloved cat, CC, when we were growing up. Often when we were driving home from somewhere, one of us would say ‘I bags CC when we get home’, which basically meant that we claimed cuddling rights to the cat. But everyone knew this was an illegitimate bagsing, because the speaker had no grounds upon which to enforce ownership or use. Thus, as soon as we got home there would be a mad scramble for the front door as each of us tried to be the first to physically claim CC.

However, while you couldn’t bags CC at the outset, you could bags being the second person to hold him (as in ‘I bags CC next’) as you jealously watched your sibling cuddling the cat. This kept relations from deteriorating into outright warfare, because we all recognised that unless we wanted a full-pitched battle,5 cuddling rights were now arbitrary—and, most importantly, temporary, so even if we didn’t get CC immediately, we’d have our chance soon enough. Why? Because bagsing, as Purchase Man notes, is intrinsically time-limited; ‘If you bags the front seat, that lasts for one journey. If you bags the “boot”, that lasts one game of Monopoly’.

So how does this help us understand she-bagging, beach cabanas and staking additional seating claims in public? Well, whether you say the words ‘bagsed’ or not, placing your bag on the seat next to you is telling everyone that you have claimed the space. However, if your bag sits on a seat on a bus or the tube, the rest of us have agreed that this is not a legitimate use of bagsing, so your attempt to claim additional space will likely be rebuffed as soon as it gets crowded. Seats at cafes, cinema and airport gates, on the other hand, are bags-able, but there are limits on how many seats you can bags and, most importantly, how long you can bags them for.

Beach cabanas clearly complicate the bagsing process. Unlike beach towels, they undermine the rules around the temporariness of bagsing, being structures that remain fixed for the entire day. And empty beach cabanas violate the rules of bagsing entirely, which is why the correct response to an empty beach cabana is simply to use it yourself. As Purchase Man notes, ‘Bagsing absolutely lapses if the bagsed item falls out of use, becomes surplus, is left over or discarded’.6

Looking back on my encounter with the schoolgirls on the tube, it’s clear that they had every right to reserve the seat. In effect, this was not she-bagging but legitimate bagsing, although neither the teacher nor I recognised this at the time. In fact, I would go further and say that if we followed the lead of children and implemented the principles of bagsing more explicitly in public space, we’d have fewer she-baggers and their equivalents at the beach.

Because at the end of the day, philosophising commentators’ claims aside, this is not about the ‘tragedy of the commons’—i.e., the tendency to deplete public resources by acting exclusively in our own self-interest. Instead, it’s about something far more significant: the sacred covenant we all agreed upon as children to respect the rules of bagsing.

Related posts

Which, sadly, was a mere stop before my own.

According to the Daily Mail, it’s called ‘she-bagging’ because the term developed as a response to accusations of ‘manspreading’. Observers pointed out that while men often take up space on transit with their bodies, women tend to take up space on transit with their bags. In my experience, he-bagging is also a thing, but she-bagging is definitely more common, probably because women are more likely to be carrying bags than men.

Well, except for those on RyanAir, where successive gate changes appear to be the norm.

As opposed to transit, where we’re more likely to say ‘Can I have this seat, please?’ or ‘Would you mind moving your bag?’ Indeed, based on a Reddit thread on the topic, a common strategy is to start to sit down—or threaten to, forcing the person to move their items out of the way or risk them being sat on.

Although it was not unheard of for one of us to wrench CC away if we felt a sibling had spent too long holding him. Our parents thought that after the novelty wore off, we would stop fighting over him, but we never did. Did we torture our cat with love? The short answer is yes, although he was surprisingly sanguine about it, presumably because being the object of our adoration made up for the occasional mauling.

I assume that at least several vacant beach cabanas have been appropriated by other beach goers. In fact, if you put up a beach cabana in the UK for use later that day, I’m pretty sure that’s the last you’d see of it—although why you would want to set up a cabana on a British beach is anyone’s guess, given that sun protection is not exactly a priority. (Nor for that matter is sitting, given that there appears to be only one beach in the country that does not consist entirely of pebbles.)