When I tell people I’m an anthropologist, I have occasionally been asked if it’s the study of ants. As Gavin Weston and his colleagues note, ‘The real-world tendency for anthropologists to be met with vacant stares when explaining their job to laypeople suggests a widespread ignorance of exactly what anthropologists do’.

Further exacerbating the problem, North American anthropology is formally comprised of four discrete disciplines: social and cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and archaeology, which share little in common beyond a general interest in humankind and our origins, having different methods, different canons and different understandings of the roots of human behaviour. Based on this broad definition, Indiana Jones, Temperance Brennan from the TV show Bones and Dian Fossey from Gorillas in the Mist are all members of the same profession, even though one searches for lost treasure, one analyses dead bodies and the other studied great apes.

Just in case you’re not confused enough, none of these fields bears any resemblance to social or cultural anthropology, the largest subfield in anthropology and the one most synonymous with the term ‘anthropologist’ itself. Occasionally combined into the godawful ‘socio-cultural’ anthropology, the two terms are generally used because those trained in the British tradition (‘social anthropologists’) don’t like to be confused with those trained in the American tradition (‘cultural anthropologists’), and vice versa. If you think this sounds petty, all I can say is that you ain’t seen nuthin’ yet.

In a 2015 study, Weston and colleagues found that social and cultural anthropologists feature primarily in horror movies, a point that continues to hold true almost a decade later, given that the last Hollywood film featuring cultural anthropologists was Midsommar. Add to this anthropologists’ notorious reluctance to engage with the public (it’s not a coincidence that most popular anthropology books are written by people from other disciplines), and you have a field that remains largely unknown to folk outside academia – and, indeed, many within it.

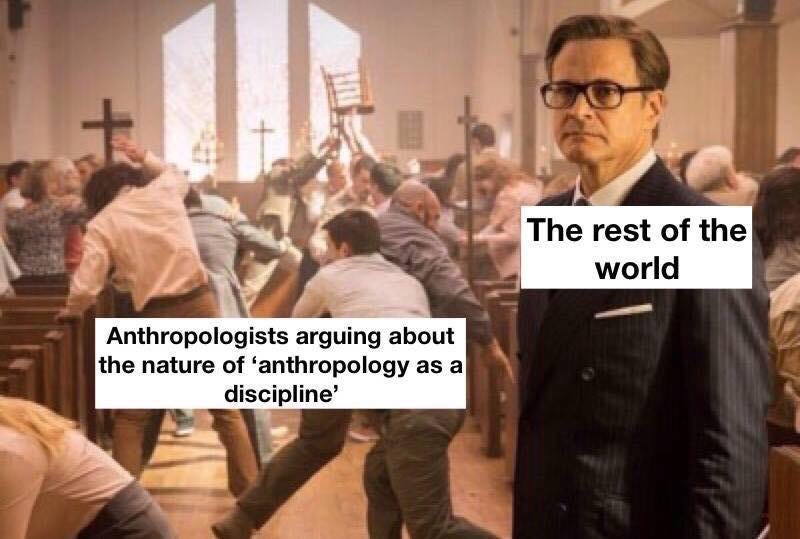

The eclecticism of anthropology as a field unified by nothing except an interest in what it is to be human creates conditions ripe for intense hostilities and rancorous disagreements. Social and cultural anthropologists are particularly prone to ferocious debates, mud-slinging and pile-ons, which mostly stem from core disagreements on the nature of the discipline.

Since the 1970s, anthropologists have agonised over the discipline’s colonial roots, whether it has more in common with the sciences or the humanities, the nature of the anthropological gaze, and so on and so forth. Quite frankly, no one is better at critiquing the discipline of anthropology than anthropologists themselves. The result is that you have a field that is poorly understood by outsiders and prone to in-fighting amongst insiders, making me wonder what Survivor would look like if it tried to rectify the lack of public knowledge about anthropology by featuring anthropologists. Inspired by James Clarke’s ‘Even TV cameras can’t excite geologists’, below is how I imagine things would go.

After their failed attempt to create a Survivor-style show featuring geologists, an American TV company decided that anthropologists might make more exciting subjects. But finding anthropologists willing to take part in the show turned out to be more challenging than they anticipated – the only person who responded to their ad was a PhD student working on a dissertation titled ‘Ethnography as reality show’, who inquired about using the show as her ‘field site’.

Never having confronted this problem before, the TV company enlisted the support of the American Anthropological Association to recruit contestants. Seeing the PR potential, the AAA obliged by putting out a call to their members, highlighting the widespread ignorance of the discipline, the opportunity the show presented to increase the public profile of the field, and pleading for volunteers.

Although they weren’t exactly overwhelmed with expressions of interest, in the end, sixteen people signed up to be contestants on the show: ten women and six men – mostly either postgraduate students and postdocs, or tenured professors and retirees, and primarily cultural anthropologists, with a few biological anthropologists and archaeologists thrown in.

The first sign of trouble occurred when they arrived at the mystery location to begin filming: the Trobriand Islands in Papua New Guinea. Three cultural anthropologists quit on the spot, declaring the location ‘problematic’ due to its association with Bronisław Malinowski and ‘anthropology’s colonial roots’. A heated discussion then ensued about whether Malinowski was or was not a colonial sympathiser before the primatologist cut short the debate with a spirited speech filled with hockey metaphors about ‘keeping sight of the net’. Placated, the thirteen remaining anthropologists proceeded to the campsite, although the primatologist later confessed on camera that he thought they were arguing about a Canadian hockey player who’d recently defected to the Anaheim Ducks.

The film crew started shooting that evening around the campfire, amidst urging from a cultural anthropologist to stop referring to filming as ‘shooting’. After an impromptu lecture by an archaeologist on the cultural significance of the number thirteen amongst the Aztecs, people began sharing war stories about their fieldwork: the grossest things they’d eaten, who’d got malaria, who’d been in a car or scooter accident, cultural faux pas they’d committed, and so on, although a heated debate started when a PhD student declared that the conversation ‘reeked of primitivism’.

The debate was soon overshadowed by an increasingly loud argument between the retired Melanesianist (that’s what he referred to himself as: ‘the Melanesianist’) and a young postdoc over his suggestion that they decamp to his tent. ‘It’s not the 1990s anymore, when we all slept with our students’, a retired archaeologist was heard to counsel the Melanesianist, in response to his repeated cries of ‘What’s got her knickers in a knot?’

All in all, the production crew felt it was a very auspicious beginning. Although slightly concerned that the audience might have trouble following some of the conversations due to anthropologists’ tendency to fling around words like ‘ontology’, ‘phenomenology’ and ‘cosmology’, their footage was exactly what they’d hoped for: obvious tension and conflict, and polarising figures the audience would love to hate.

Tensions continued to escalate during the week and two factions quickly emerged, separated primarily along generational lines, although the cultural anthropologists seemed to find some common ground over ‘fieldwork’, with many taking to following the film crew around, asking them questions, and taking notes on what they observed. Still, this caused numerous headaches for the production crew, because it meant that contestants couldn’t be filmed without also inadvertently filming the crew themselves.

Then it came time to vote someone off the island. Members of faction A read out an open letter enumerating the faults of faction B and tried to vote them all off the island. At this point, the director stepped in to explain that they could only vote one person off. They unanimously chose the Melanesianist. Faction B, after insisting on the right to read out their own counter open letter enumerating the faults of faction A, agreed with their choice.

The following week, the director decided to break up the two factions into tribes to force them to work together. As all the anthropologists strongly objected to the term ‘tribe’ itself, the strategy worked for about ten minutes, but the truce fell apart shortly afterwards when two members of one tribe got into a screaming match over whether ‘manpower’ could ever be employed as a gender-neutral term. By the middle of the week, the two factions were spending most of their time in intense huddles, and it was clear that further counter-counter letters and counter-counter-counter letters were in the offing.

Making matters worse, tensions had now sprung up between the film crew, primarily because some were annoyed by all the attention that cameraman #2 and a boom operator were receiving from the anthropologists, and complained to the director that they were spending too much time talking about their jobs and not enough time doing them. Plus, interviews with the anthropologists had sensitised crew members to unsatisfactory aspects of their work conditions and several members of the production crew were now openly discussing the need for strike action.

After both the boom operator and an assistant sound editor asked for a raise, in a bid to quell the open letters and the anthropologists’ fieldwork with the crew, the director announced an immediate ban on all writing tools. Four anthropologists quit on the spot, outraged by the ‘unconscionable act of censorship’.

When it came time to vote someone off the island, the director announced that there would be no votes cast that week due to the high volume of departures, but the archaeologists and primatologist begged to leave anyway.

At the start of week three, now down to just five participants, the director announced that all remaining contestants would take part in a canoe race retracing the path of the Kula ring: the ceremonial exchange system made famous by Malinowski. Outraged by what was universally deemed an insensitive act of cultural appropriation, four more anthropologists quit on the spot. The last remaining anthropologist – the PhD student writing about reality shows – was declared the winner by default.

The director is still going over the recordings to see what can be salvaged – not much as it turns out, because the film crew appear in most of the footage, and their new union is demanding actors’ rates for any appearances. Meanwhile, the PhD student has turned her dissertation into an auto-ethnography focusing on her lived experience of being filmed. It’s called ‘Your real(ity) min(e)d’. (Yeah, I don’t understand the title, either, but she’s a post-structuralist with a phenomenological bent, so that’s par for the course.)

So anthropologists, like geologists, will remain an enigma. The TV company is tentatively looking into the possibility of doing a show featuring sociologists, on the premise that they can’t possibly be worse subjects than anthropologists.

I really wish I could make some comment that continues in the same vein as this brilliant piece, but as physicist, I find that when I reach deep, deep down into my own experiences they just can't compare with any of this.